The mythology of the Middle Income Trap

A term that has been popular lately among economists and other people closely involved with economics is the “middle-income trap.” It is the idea that there is a natural tendency for many developing countries to develop at a fast pace until they reach an income level of around 20% to 35% of the most advanced economies. Then they supposedly tend to stagnate at a constant income level relative to the most advanced economies.

This is fundamentally a superstition: there is no scientific foundation in economic theory for the claim that such income levels might be a natural “resting point” for developing countries in general. Factors such as institutional quality and tax regimes indeed change the level of income countries tend to converge towards, so countries with poor institutions and high and poorly designed taxes will tend to converge to lower levels of output per capita. But there is no magical reason why the natural income levels for most countries should be 20-35% of the income levels of the most advanced countries.

What is observed empirically is that there are indeed dozens of countries with incomes around 20% to 35% of the incomes of advanced economies, and these countries often do not grow very fast. However, this applies to countries of every income group: the countries that grow very fast, as China did from the 1980s until the early 2010s, are rare cases (there is a theoretical justification for this: as countries tend to converge to their natural level of development, the proportion of time they spend during their process of convergence would tend to zero as the time-frame increases).

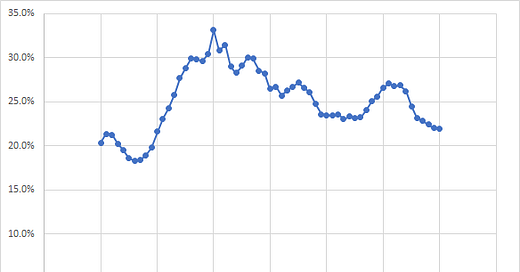

Let us consider the case of a country that I know well: Brazil. In terms of GDP per working-age population relative to the US, the data says it increased from 20% in 1960 and reached 33% in 1980. Then, over the next four decades, Brazilian GDP per working age population has had a tendency to slowly decline relative to the US, reaching only 22% in 2020:

This data has been computed using the 1975 and 2017 benchmarks of real income levels across countries produced by the International Comparison Program. I used two benchmarks because if you extrapolate the official GDP time series from a single benchmark (like extrapolating relative Brazil/US income levels in 2017 back to 1960), the two-time series tend to diverge substantially from direct benchmarks, given the usual problems with long-run GDP estimation.

The anatomy of Brazilian underdevelopment

It is a well-established consensus among economists that the main component that explains the discrepancy in levels of output per working-age population across countries is total factor productivity. In Brazil’s case, a quick glance at the basic statistics of employment reveals the huge structural misallocation of labor: while the working age population of Brazil is ca. 145 million, this labor force is tremendously underutilized as only 33 million Brazilians work in formal jobs for companies. So, what are the other 110 million working-age Brazilians doing?

There are 30 million Brazilians classified as “entrepreneurs,” 95% of whom are not people who own firms but people who lack formal employment and so try to obtain their subsistence from informal gigs. There is also a substantial population of several million people formally employed as domestic workers for families instead of firms, although most domestic workers in Brazil are informal and so classified as being among those 30 million self-employed “entrepreneurs.” We also have 12 million workers employed directly by the government, which means that for each 2.8 Brazilians who work in formal jobs for firms that pay taxes, there is one Brazilian officially employed by the government from those taxes. In addition, there are 36 million Brazilians who are officially “retired” and so receive government pensions, a number slightly larger than total formal employment in firms!

Thus, taxes are ultimately paid from the output of firms employing 33 million people, and these taxes directly support 48 million people working either for the government or who are retired. In fact, given Brazil’s 33 million formal firm workers include a lot of dispersion in productivity, it is fair to expect that almost the totality of economic activity in Brazil is ultimately generated by high productivity firms employing between 20 to 25 million workers, out of the working population of ca. 145 million. This is the main explanation for why Brazil’s GDP per working-age population is so low.

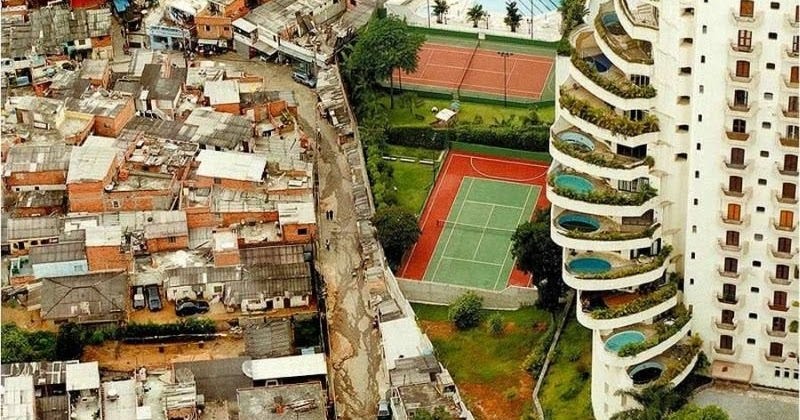

The political economy of Calidesh

Brazil can be best understood as a mix of two societies: imagine if California (pop. 39 million) left the US and instead merged with Bangladesh (pop. 169 million), and the two territories became a country of 208 million people, Calidesh. This country would have a similar population and GDP as Brazil. The distribution of productivity across the population would also be similar, given that in Brazil, most economic activity is generated by only 15% of the working-age population.

Imagine if Calidesh were a democracy. What would that imply? It is not hard to see the natural political equilibrium: the 169 million from the former country of Bangladesh would be 80% of the electorate, and most of these would vote to tax and redistribute the output produced by the high-productivity workers of the former state of California.

In Brazil’s case, its recent economic history can be summarized as follows: the country was under a strict military dictatorship from 1964 to the mid-1970s, a period when output per capita doubled. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, there was a slow process of re-democratization that culminated with the end of military rule in 1985. During the present democratic period from 1985 to 2021, GDP per working-age population has stagnated, growing at less than 1% per year. However, central government expenditures have not stagnated since 1985. In fact, real expenditures per capita more than doubled since 1985, as the Brazilian state has developed the largest social-welfare programs among all developing countries: just from 2005 to 2015, the real wages of the public sector workers increased by 50%.

This situation was a natural consequence of the combination of a democratic form of government with the economic anatomy of “Calidesh”: as the country became focused on rent-seeking meant that economic development was suffocated. This was fundamentally not a problem to most Brazilians since around 80% of the population could benefit more from increasing transfers from the high-productivity sector rather than from broad-based economic progress, at least for the first three decades since 1985.

One curious fact is that Brazil’s rent-seeking model of “development” did not decrease income inequality substantially, as the Gini index decreased from 0.58 in 1981 to 0.54 in 2019:

This failure to reduce inequality despite ballooning government expenditures on social programs was a consequence of another fact: the distribution of rents accruing from rent-seeking is also highly dispersed, with Federal and State job openings paying 10 to 30 times the minimum wage. In contrast, the state provided a minimum income transfer for the unemployed poor at around 15-20% of the minimum wage. Several of the most talented colleagues I had in college are now public servants performing those nice “public servant” jobs paying over a dozen times the minimum wage.

Brazil’s “rent-seeking model of development” had its golden age from the late 1980s until the mid-2010s. By that point in time, as government expenditures approached 40% of GDP and had no perspective of slowing down, there was a massive fiscal crisis that culminated in the largest recorded recession in Brazilian history: from late 2014 to early 2016, GDP declined by nearly 8.2%.

In 2016, the current administration was impeached, and a new macroeconomic policy regime started to take shape: the focus shifted from a rent-seeking model of “development” toward a model of macroeconomic policy regime with a little more emphasis on actual broad-based economic progress. However, the fact remains that the political economy constraints and incentives of Brazil still strongly tend toward a policy framework focused on rent-seeking. Thus, it is likely that from now on, we will have a macro-policy regime characterized by lower rates of growth in government expenditure but also modest rates of economic growth, with the growth in government expenditures fundamentally constrained by the exhaustion of the capacity for the private sector to support further increases. TFP convergence to developed countries in the broad economy will continue to be constrained by the massive rent-seeking structure that has been consolidating over the last four decades. That is so because a more serious shift toward a model of economic organization based on broad development would require going against the interests of the large fraction of the population where government transfers consist of most of their incomes.

Are there reasons to expect Brazil to get out of its trap?

Brazil might get out of this trap if the population perceives that we are reaching a point of exhaustion in the returns from rent-seeking the output they can tax from the 15% highly productive component of the working population. The fact that Brazil still has an extremely high Gini index despite increasing government expenditures to nearly 40% of GDP suggests that the returns of this “development strategy” might be low for people without access to the best-paid government jobs and/or contacts. Then their expectations of improving their standards of living might shift to a policy of broad-based growth that focuses on increasing the returns on productive activity of firms. The policy shifts since 2016 might indicate a tendency for continuing reforms that might allow for a robust trend in economic development. Still, it is impossible to know what the future might hold.

Are you sure the problem is TFP which is about structure and learning curves. It could be low capital spending that is limiting economic growth. Brazil has lots of cheap labor, so it doesn't always make business sense to invest in equipment. Why buy a Roomba when maids are cheap? Brazil also has extensive natural resources, so the "resource curse", the ability to earn a lot of money by extraction, may be holding Brazil back as well.

One thing high income countries tend to have is high internal demand. Most people have salaries large enough to buy lots of goods and services. This is surprisingly hard to develop. China started running into this problem maybe five years ago. Building a well off consumer society presents political risks. It is hard to distribute economic power without also distributing political power. There's a reason the slave owning South in the US fought against settling the western territories and the Homestead Act was only passed during the Civil War. Having an economic say makes people "uppity".

There's a problem at the other end as well. Rich people don't like to pay taxes. If you look at things historically, the US had a much higher rate of economic growth back when taxes were outrageous than after they were lowered to more sensible levels. Similarly, most blue states which are anti-business, if only because they tend to tax businesses a lot, tend to have higher GDP per capita rates than red states which are pro-business and tend to have lower taxes.

It's not impossible that Brazil's big problems might be that taxes are too low, the government is not spending enough of infrastructure and human capital and the financial sector is politically and structurally constrained in its investments.

great commentary.