Democracy and development

It appears to be the case that the foremost causal factor in social and economy development is democracy

Democracy, what?

First, to talk about democracy, one needs to define it. It reminds me of a conversation I had with a friend from Singapore who claimed that Singapore was certainly a democracy because there are elections. However, I and others in the conversation pointed out that democracy is more than just elections; we asked if there was freedom of the press, for example. The point is that democracy is hard to define. Here I define democracy as an idealized situation.

I define democracy as follows: Suppose there is a state, an organization with a monopoly on the use of violence inside a territory. A pure democracy is when the power to control the state (that is, political authority) is perfectly dispersed across the population. A pure autocracy is when the political authority fully concentrates on one individual. No pure autocracy has ever existed, as well as no pure democracy. All present and historical states exist in a continuum from pure democracy to pure autocracy.

Historical examples of democracies and autocracies

Even the most brutal dictators, like Stalin, could not hold power without control of the media and an ideological propaganda machine, which means that ideological consent was necessary for them to maintain power. Since the Pharaohs of Ancient Egypt, there was an ideological foundation to justify the power of the rulers. For example, there was a general acceptance of the idea that ancient Chinese emperors had a “mandate of heaven” to rule over the entire population of the Chinese world. This is why freedom of speech is a defining feature of democracy: it means that nobody has the right to control the ideological narrative.

Among democracies, I think we can classify Classical Athens as the closest to the ideal of pure democracy among well-documented states across all of history up to the present. Although the Athenian state excluded women from political participation and had a substantial proportion of slaves in the population, the degree of dispersion of political authority across free adult males was functionally perfect. Each citizen was equal to any other in terms of their expected political authority, as explained by Aristotle:

Democracy arose from the idea that those who are equal in any respect are equal absolutely. All are alike free, therefore they claim that all are free absolutely... The next is when the democrats, on the grounds that they are all equal, claim equal participation in everything. (Aristotle, Politics)

For comparison, in modern representative democracies, elected individuals have an enormously greater influence on state policy than non-elected individuals. Also, the likelihood an individual can get elected varies enormously across individuals. In any modern democracy, an experienced politician with connections or a billionaire has a much greater likelihood of being elected to any political office than the average citizen. Because of these factors, Aristotle classified elections as being inherently anti-democratic, instead characteristic of oligarchies, that is, states ruled by elite groups:

It is accepted as democratic when public offices are allocated by lot; and as oligarchic when they are filled by election. (Aristotle, Politics)

Thus, all political offices in Athens were filled by sortition from the citizen population. Major policies could only be implemented by popular assemblies open to all citizens and approved with the explicit majority of the vote of participating citizens. Participation was also voluntary, so citizens who didn’t vote, for instance, in the proposal of invading Syracuse, could be drafted into the Syracusan expedition if it was approved.

The Roman Republic was a state more like our modern democracies than Classical Athens. While Roman citizens lacked equal political rights (the votes of members of elite groups had much greater weight in the popular assemblies which elected public officials), it was a system of representative government with universal male suffrage among Roman citizens. The Greek political philosophers classified Rome as a mixed system, not quite a democracy but not really an oligarchy.

All ancient democracies were tiny city-states: the Roman Republic was likely the largest ancient city-state to ever exist, had about 300,000 (adult male) citizens, Athens peaked at around 60,000 citizens, and it was among the largest city-states. Other major city-states, like Sparta, had 8,000, and Corinth had 10,000 to 15,000 citizens. The median ancient city-state was much smaller: a small town of 500-600 houses, with about one thousand adult male citizens living in the town and the surrounding countryside.

As Rome’s empire consolidated, the former city-state incorporated the whole population of Italy as citizens. Rome’s citizen population increased fifteen-fold from the early 1st century BC to the early 1st century AD (from 300,000 to close to 5 million, some historians think this massive expansion was also explained by the inclusion of women in their censuses). By that point, Rome was thousands of times bigger than a typical ancient city-state; it became what could be perhaps called the world’s first nation-state. But, at the same time, its republican form of government, which required face-to-face participation in the popular assemblies, collapsed, and Rome became an autocracy under a single ruler, the Roman Empire.

The first state that could be categorized as a democracy that ruled over a large territory, larger than one city and its hinterland, and was relatively stable, would have to wait two thousand years: the United States by the late 18th century. It was the modern concept of representative democracy with paid professional politicians and local districts who elected representatives that enabled this form of regime. Today, over a hundred countries are representative democracies structured similarly to the American prototype. But it is true that in antiquity, the concept of representing the population of a geographical territory through representatives from districts was also known but executed at a much smaller scale: Ancient Athens had 139 districts (“demes”), and each district sorted citizens as representatives to their council of 500 citizens.

Democracy and development

In small societies such as (mostly) self-sufficient agricultural villages where everyone knows everyone else, there is no need for a legal system to protect private property and enforce contracts: as the quantity of information each person needs to work with is small, economic relations can be based on trust. However, the degree of both division of labor and technological complexity is severely limited when the scope of interaction is only the people you personally know.

The emergence of states did not change this situation: the typical pre-modern state was a stationary bandit (think of a Mongol horde that decided to settle in and regularly tax the villages they conquered instead of plundering them sporadically) that did not include the conquered population into their legal framework: their subjected population were subjects, not citizens. Thus, there were no incentives for the state to provide institutions that allowed large-scale functioning of markets, such as a regime of the rule of law and contract enforcement. This is what caused the general lack of technological and economic sophistication of pre-modern societies.

After there was some degree of democratic inclusion and subjects became citizens, the apparatus of coercion and compulsion of the state began to be tamed by the population that it had subjected. Now, the state could be used to protect property rights and enforce contracts between citizens; this allowed the division of labor between anonymous people and, therefore, a much greater increase in the scale of the division of labor and, therefore, technological sophistication.

Some economists think there exists a division between “Smithian” gains from the division of labor and “Schumpeterian” gains from technological innovation, but in reality, they are both one and the same: a larger population covered by a legal system that enforces property and contracts allows for a greater quantity of ideas to be integrated into a large system of division of labor. This fact has already been understood by specialists in the theory of economic growth.

The possibility of massive economic flourishing above the pre-modern standard of the self-sufficient village was already made apparent in the small scale of Ancient Greek democracies and oligarchies (which also featured a substantially higher degree of popular inclusion than typical pre-modern autocracies), as I have detailed extensively in other posts. But it was over the last few centuries, with the development of what Acemoglu and Robison call inclusive institutions (i.e., democracies and relatively open autocracies like Singapore) covering at first hundreds of millions and then billions of people, that mankind’s true potential through integration into a global system of division of labor flourished, what Hayek called the “extended order.”

Also, this line of reasoning suggests that contrary to what some libertarians claim, there is no inherent contradiction between democracy and economic freedom. In fact, the evidence suggests the two have been linked since antiquity. Democracy is not the tyranny of the majority but the taming of the state by the individual members of the population who were previously subjected to its autocratic tyranny.

Democracy and modern economic growth

It was over the decades following the American and French revolutions, at the same time as the first modern democracies were set up, that modern economic growth began by the 1820s and 1830s. That was the time at which the speed at which new technologies were invented, that cities grew, and other indicators of aggregate output reached modern rates of growth in North America and Western Europe.

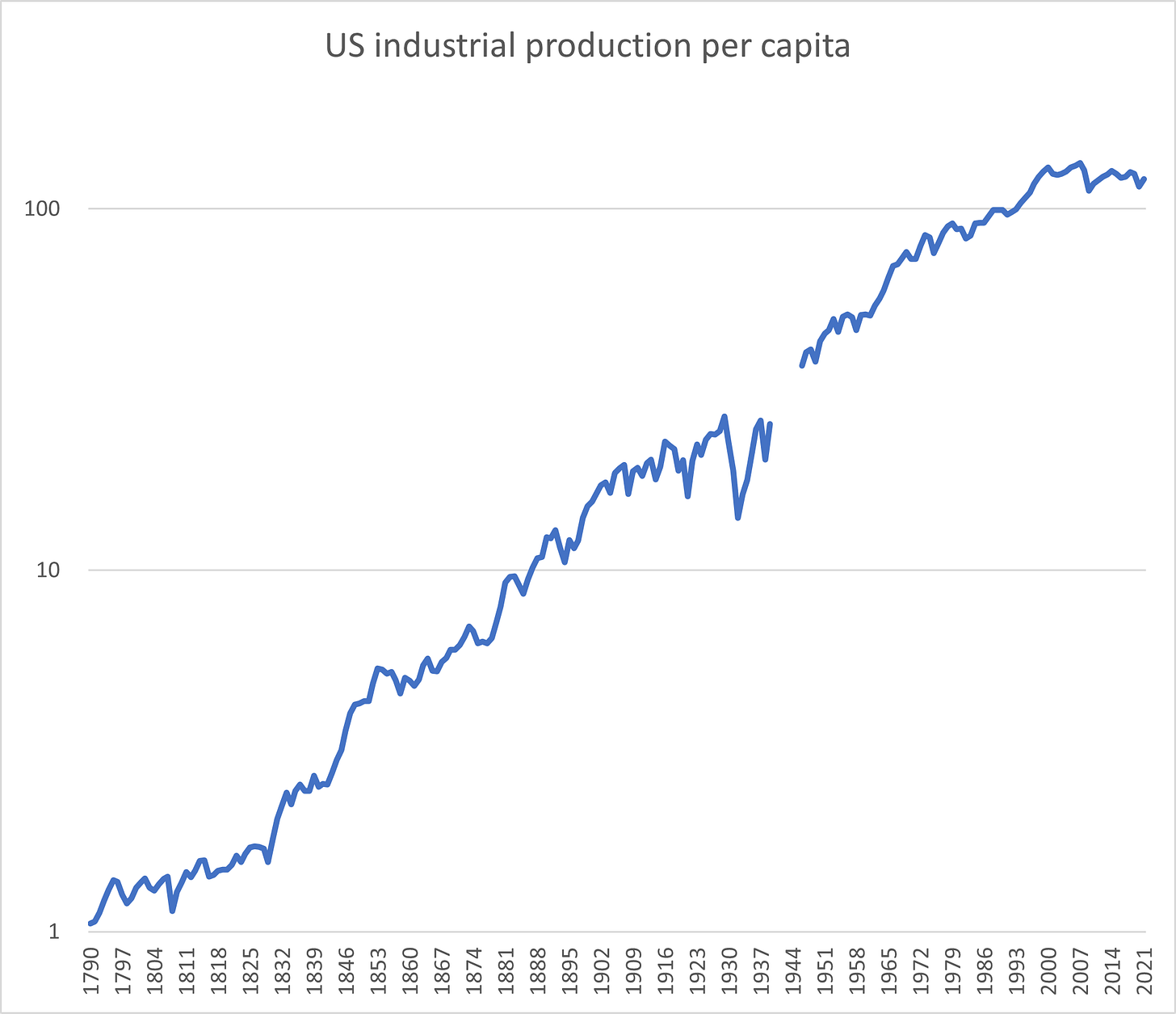

For example, US industrial production per capita was growing at 1.3-1.4% a year from 1790 to 1830; then it started growing at 2.7% per capita in the 1830s, and very fast growth continued until the early 1970s, then the growth rate of industrial production per capita has fallen to less than 1% over the past half a century (considering the dramatic rise of imports in manufactured goods, domestic consumption of industrial output has grown at around 1.5%):

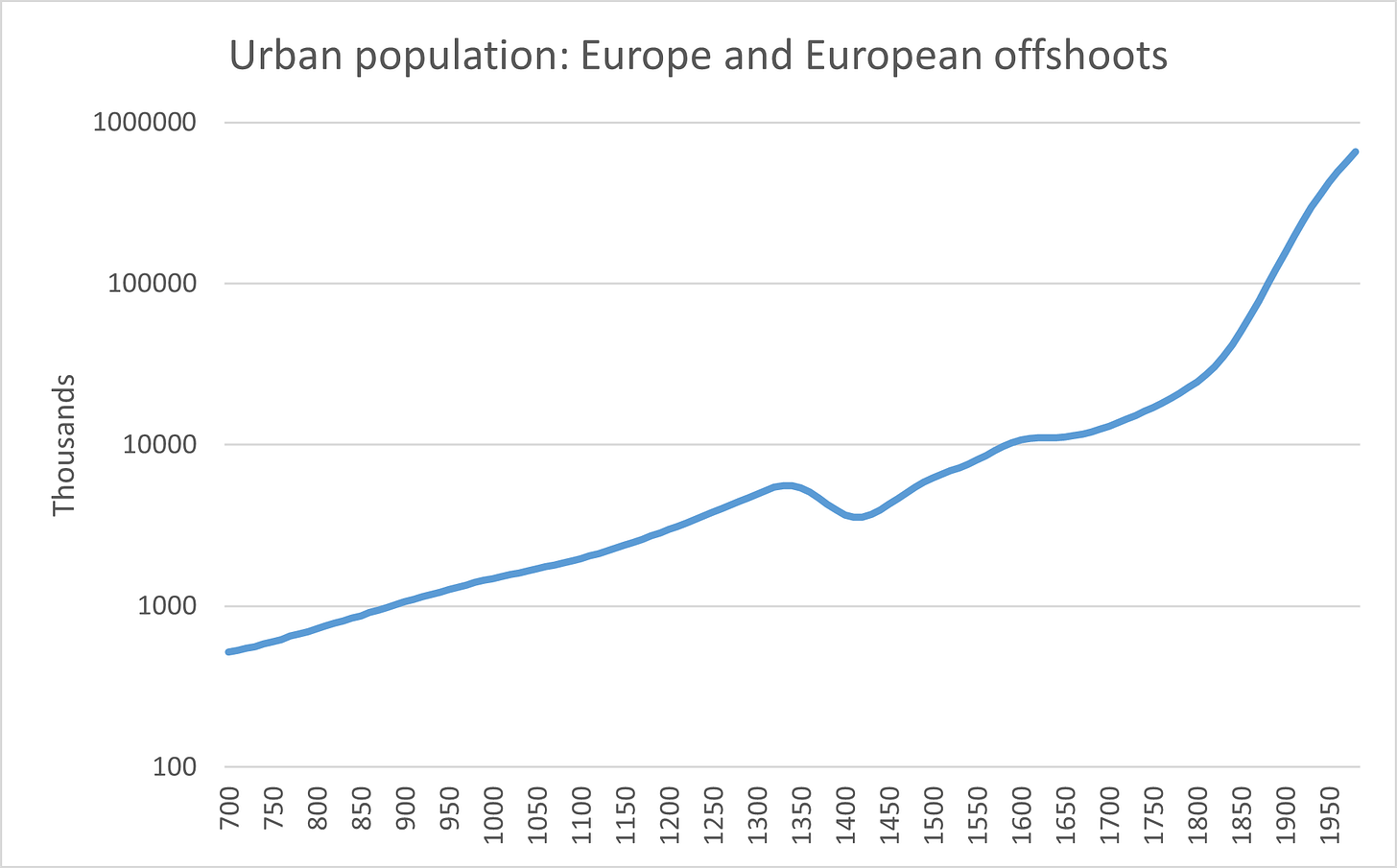

The rate of growth of the urban population of Europe and its settlement colonies (US, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand) also exploded in the early 19th century up to the late 20th century, as most people were living in cities of at least 5,000 inhabitants. Urbanization is a symptom of a shift from a society of self-sufficient villages to a society of people employed in a more sophisticated system of division of labor.

Although one should notice that economic growth did exist before the early 19th century, it was much slower: the growth rate in the urban population of Europe was 0.35% from the 8th century to the mid-18th century. Over this millennium, Europe’s urban population increased from about two-thirds of a million to over 15 million by the mid-18th century. While slow compared to modern standards, the pre-modern process of European urbanization was comparatively highly dynamic. Consider a gold standard for pre-modern autocracy: Imperial China; it is estimated its urban population (in cities over 10,000) increased at a glacial pace, from an estimated 2 to 3 million in the 8th century to around 6 or 7 million by the early 18th century, without any increase in the rate of urbanization which fluctuated around 3 to 4%. The global trend of increasing urbanization did not occur until the 19th century: Although we lack good quality estimates, it appears that Bronze Age Mesopotamia was more urbanized than most countries of the world in the early 19th century.

By the late 18th century, European urban growth dramatically increased, more than doubling to 0.9% from 1750 to 1830 and further doubling to 2.0% from 1830 to 1980 (considering the growth of the urban population in its offshoots in North America and Australasia), when the “western” urban population reached two-thirds of a billion. Today, as the population in European countries and their offshoots are either tending towards stagnation or collapse, urban populations also stopped increasing. Now it is quite possible that we are currently at the peak of the western urban population, with roughly 1 billion people living in towns and cities with over 5,000 inhabitants in Europe, North America, and Australasia.

While some people argue it was the British Industrial revolution that started modern economic growth, it is apparent that urban populations started increasing at faster rates across Europe and its colonies as a whole. In addition, the latest estimates of historical national accounts imply that France, once thought to not have begun industrializing until the late 19th century, experienced almost the exact same growth trajectory as Britain from the late 18th century to the late 19th century. In both cases, growth rates reached modern levels in the decades after the Napoleonic Wars (which ended in 1815):

With the current collapse in the population growth of democratic countries and the lack of tendency for the expansion of democracy in authoritarian regimes like Russia and China (economic growth in both of which are already stagnant in the last few years despite having income levels at a fraction of Western levels), our extended order is not growing as fast as it used to be, so I suspect that exceptional progress mankind has made over the last 200 years will not continue at comparable rates over the foreseeable future. Well, the quantitative evidence suggests it has already slowed down in North America and Western Europe since the 1970s: Modern economic growth is quickly becoming historical economic growth.