On the economic performance of different periods of antiquity

The evidence appears to suggest that the politically decentralized Classical Greek world was substantially wealthier than the centralized Roman Empire

Recent research regarding ancient economic history has suggested that Western Eurasia during the time it was politically unified under the Roman Empire, achieved an extraordinarily high level of economic prosperity for a pre-modern society. As Peter Temin (2006) noted, it took nearly two thousand years for a comparable level of prosperity to be achieved in the Western world:

All societies organize their economic functions through a mixture of redistribution, reciprocity and market exchange. From an economic point of view, the important characteristic of the early Roman Empire was the relatively large role played by market forces, certainly as compared to the medieval economy that would follow. Large-scale production and movements of resources in the early Roman Empire were dominated by markets. This mode of organization promoted the exploitation of comparative advantage, helped by political stability, personal security, and widespread education. It also promoted a modest rate of economic growth that resulted in the prosperity of the early Roman Empire, which was not to be equaled in the West for almost two millennia thereafter. (p. 149)

However, as noted in many recent works of world economic history, it appears to be a necessary condition for fast economic growth for civilization as a whole to be organized in a decentralized system of sovereign states instead of a centralized state like the Roman Empire. The basic argument is that competition between states produces a tendency for institutional improvement and for the maintenance of inclusive institutions. Thus, the prosperity of the Early Roman Empire appears to be a counter-example to this thesis.

However, as we will see, the empirical evidence will help us to reconcile this apparent contradiction: when the ancient world was divided into many small sovereign states (Polis or city-states) during the period from the 9th century BC until the 3rd century BC, the current state of evidence suggests its performance was superior to the Roman period. Also, the region of the ancient world that was the most prosperous before the Roman conquest, the lands around the Aegean, became less prosperous after the Roman conquest.

Brief historical outline

The western notion of antiquity can be understood as the period of history in Western Eurasia (Europe, North Africa, and Western Asia) from the 8th century BC, the time of Homer, the first Olympiad, and the Founding of Rome, to the final collapse of the Roman world under the Arab invasions of the mid-7th century AD.

From 800 BC to 200 BC, this world was restricted to the lands that bordered the Mediterranean and mainly politically organized into small kingdoms and city-states, most of which were Greek-speaking but it also included city-states of Italic and Phoenician cultural backgrounds such as Rome and Carthage. While the kingdom of Macedon under Phillip II and Alexander the Great achieved hegemony over most of the Greek city-states in the late 4th century BC, this hegemony did not last long and these cities were never formally incorporated into a centralized State (Ober (2015)).

It was only with the consolidation of Roman hegemony following a sequence of wars in the late 3rd and early 2nd centuries BC that a genuine process of political unification of this world into a single state began. By the mid-2nd century BC, from the perspective of the inhabitants of the city-states around the Mediterranean, Rome already conquered their world. As the Greek historian and political philosopher Polybius wrote around 150 BC:

“The Roman conquest, on the other hand, was not partial. Nearly the whole inhabited world was reduced by them to obedience: and they left behind them an empire not to be paralleled in the past or rivalled in the future.” Polybius, Histories, book 1, Importance and Magnitude of the Subject (tufts.edu)

Roman domination over the ancient world was maintained for the next 800 years, even the collapse of the western half of the Roman Empire in 476 AD did not end it: a few decades later, most of these territories were re-annexed by the surviving eastern half of the Empire. It was only with the Arab invasions of the 7th century AD that we can say that this Rome-dominated world ceased to exist: The Arabs conquered the lower half of the Roman Empire which severely weakened the Roman state, to the point it was unable to hold on its European territories as well, thus ending the dominance of a single state in Western Eurasia.

Evidence of the degree of urbanization: the urban footprint

We want to compare the Classical and Early Hellenistic world (500 BC to 200 BC), before Roman dominance, with the Imperial Roman world (100 BC to 300 AD) after Rome had consolidated its power.

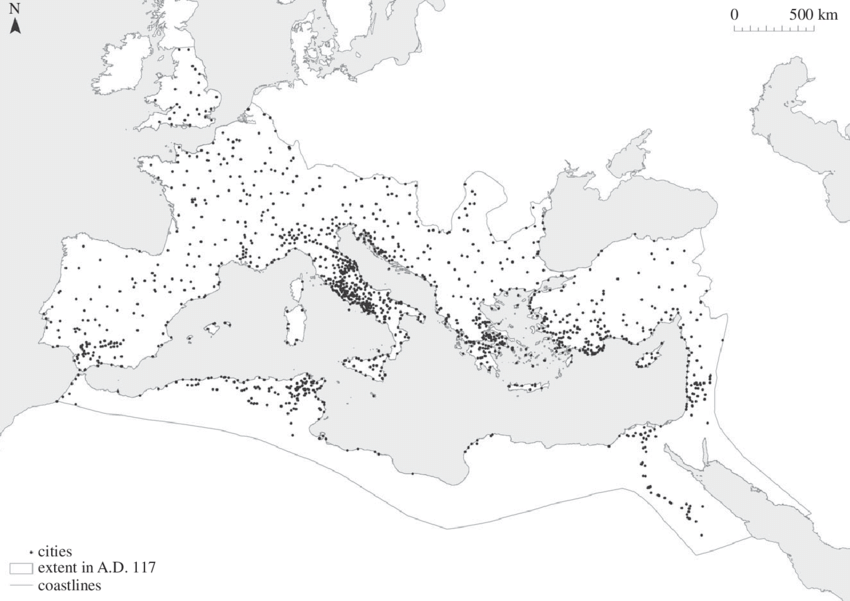

Let us begin with the best macro-level evidence that we currently have: the size and number of cities. In the late 4th century BC, when the population of Classical Greek civilization peaked, we know of 1,035 Greek city-states from the polis inventory (Hansen and Nielsen (2005)), and we know of 1,388 Roman cities during the Early Roman Empire from the inventory of Roman cities of Hanson (2016).

Among the 1,035 Greek cities, from archeological studies, we know how big 232 of these cities were in terms of the area of their urban physical footprint as implied by the area enclosed by their city walls: on average, they occupied 78 hectares. To estimate the population of the whole sample of over a thousand cities, Hanson (2006) corrected for the overrepresentation of large cities that archeologists are more likely to study; thus, he estimated that the mean size was 51 hectares.

For the Roman-period cities, Hanson provides estimates of the walled areas of 375 of these 1,388 cities (for the hundreds of other cities he provides estimates for the area occupied by the city-grid or the area occupied by residential buildings, but we want to compare apples to apples here), which yields an average walled area of 46 hectares, unlike Hanson (2006), he does not believe there is an overrepresentation of large cities (in fact, many of the largest cities like Rome and Alexandria lacked any defensive walls during the imperial period) thus it is likely the average Roman city size by walled area was close to 50 hectares, identical to Hansen’s estimated average city size in the Greek world during the late 4th century BC.

Thus, the typical geographical size of cities of the Roman Empire was similar to the size of typical Greek cities. However, they appear to be only 40% more numerous. It is estimated that the Roman Empire had a population of 60 to 75 million people in the 2nd century AD, while the Classical Greek world had a population of 8 to 10 million people in the 4th century BC. Thus, it appears that there were roughly six times more urban spaces in proportion to the total population in the Classical Greek world than in the Roman Empire. This meant that either the rate of urbanization was much higher or the Greek cities were less crowded, or both.

In fact, Ober (2015) suggests that considering the population living in towns over 5,000 inhabitants shows that the Classical Greek world had about 2.5 to 3 times the rate of urbanization of the Roman Empire, which suggests a higher per capita income. Additionally, the density of Roman cities as estimated by archeologists was approximately 2.5 higher (70 persons per hectare of the walled area in 4th century BC Greece, compared to 180 persons per hectare in the Roman Empire), which suggests a lower level of income for urban residents: similarly how cities in developing countries today are much more crowded than cities in the US or wealthy European countries.

It is true that we are, to a certain degree, comparing apples to oranges: the Greek-speaking world of the 4th century BC corresponded to a smaller proportion of the population of the ancient world than the Roman Empire did in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD: By the 1st century AD, Rome had conquered many lands that were once considered barbarian territories outside of what educated Greeks as Polybius considered the “inhabited world,” such as most of Western Europe. Instead, one might argue that we should compare these prosperous city-states with the richest parts of the Roman Empire.

It is widely accepted that Italy was among the most prosperous regions of the Roman Empire (the other regions that appear richer than the average for the Roman period include the Aegean and North Africa). In Italy, there were 377 cities surveyed in Hanson (2016), and we have measures of the walled areas of 87 of such cities, with the average measured size being 31 hectares, smaller than the typical size of cities in the provinces. However, Rome itself is not included in this sample: Early Imperial Rome did not have walls. In Late Antiquity, due to the barbarian invasions, it had walls enclosing 1,370 hectares, but the city had declined in size from its peak in the 1st and 2nd centuries. We might conservatively guess that if Early Imperial Rome had walls, they would likely enclosed ca. 2,000 to 2,500 hectares: Classical Athens had walls enclosing 211 hectares, and its estimated residential areas covered about 120 to 150 hectares of these areas, the area of Imperial Rome’s 14 administrative districts is estimated at 1,800 hectares and this area is believed to be fully covered by residential areas in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. Thus, this hypothetical walled Rome would raise the average size of the 377 Roman Italian cities by 20% to 25%, to ca. 40 hectares, closer to the imperial average of 46.

The population of Roman Italy in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD is estimated at between 8 to 13 million (similar in overall magnitude to the Classical Greek world in the 4th century BC), with 15,000 hectares of urban land housing close to 3 million city-dwellers. Thus, Roman Italy apparently had 1,150 to 1,900 hectares of urban space per million inhabitants compared to 850 to 1,050 hectares for the empire as a whole. In the 4th century BC, the Greek-speaking world had 5,300 to 6,600 hectares of urban space per million inhabitants. This suggests that Roman Italy was moderately richer than the Roman Empire as a whole but that the Classical Greek world was much richer than both.

Standards of housing

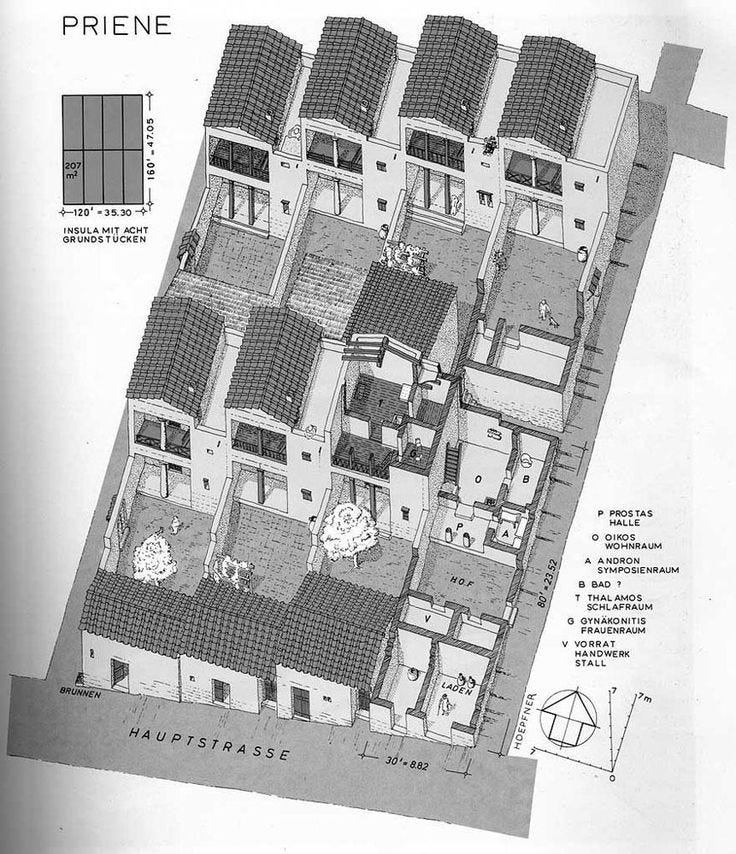

As urban population densities were higher in the Roman period, the typical amount of housing space per capita was smaller. In Late Classical Greece, towns were built according to standardized blocks with between 6 to 12 houses in each block:

To make his demographic estimates, Hansen (2006) shows that houses in Late Classical Greece typically covered 175 to 250 square meters on the first floor (in the town of Priene, for example, the standard houses covered 207 square meters). Morris (2004) finds 230 square meters to be the median size of the ground floor in the 4th century BC and that the median size of the area of the first floor increased by a factor of five since the 8th century BC when the median Greek house typically occupied only 50 square meters. He also argues that houses with two floors became common in the 5th and 4th centuries BC, which increased the average interior space per house by 50%. Thus, the typical Late Classical and Early Hellenistic Greek house was about seven times larger than in the 8th century BC and had 250 to 350 square meters of interior space, more than the average American home today.

To estimate how much residential space was available on a per capita basis, Hansen estimates that on average, a household consisted of a family of 4.5 to 5.5 people plus 0.5 slaves. This implies Classical Greeks urban dwellers typically enjoyed 45 to 65 square meters of residential space per capita. For comparison, in the US today, the average residential space per capita is about 75 square meters, and in France and Germany, it is 40 square meters, in the UK, it is 30 square meters, while in developing countries like Russia and China, per capita residential space is between 15 to 20 square meters.

As Hansen (2006) notes, the majority of the population of the Greek city-states resided in towns: with the median Greek city-state being a town of 3,000-4,000 inhabitants with a rural area of 1,000 to 2,000 inhabitants (Priene and Olynthus had 35 and 37 hectares of walled area and thus were close to the median size). Thus, urban housing standards are representative of the ancient Greek population as a whole which allows us to conclude that the inhabitants of Classical Greece enjoyed a similar amount of private residential space as the inhabitants of developed countries today.

For Rome, the evidence from the best-documented city of Pompeii suggests there were an estimated 1,400-1,500 household units and a total population of 11,000-12,000. Thus, it appears there were around 7 to 8 persons per household as around a third of the population consisted of slaves: Roman Italy was likely the society in human history that practiced slavery on the broadest scale, according to Schiedel (2019).

According to Stephan (2013), during the Roman Imperial period in Italy, the median size of the ground floor of houses excavated in towns like Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Ostia, was 168 square meters. Many Roman houses had two floors, so if we assume that the proportion of space on the second floor compared to the first is the same as in Classical Greece (ca. 50%), that implies a per capita residential space of 30-35 square meters if houses had 7 to 8 inhabitants, one-third to one-half smaller than the residential space per capita estimated for Classical Greece. This is consistent with its higher estimated population density: Pompeii covered 65 hectares, with a population density of 150 to 170 inhabitants per hectare, which was typical of a Roman-era city and about twice the typical density inside city walls estimated in Classical Greece.

Also, we have to take into consideration that unlike in Classical Greece, most people in the Roman period did not live in towns but lived in the countryside. Therefore, the high standards of Roman urban housing in prosperous towns like Pompeii and Herculaneum were not representative of the majority of the population. For other regions of the Roman Empire, which were poorer than Italy, there is rural housing evidence that suggests standards similar to Archaic Greece: Roman Egypt, thanks to the dry climate, has preserved more evidence than other provinces of the Roman Empire. Typical housing units found in Roman-period Egyptian towns and villages were around 60 to 70 square meters (Kron (2015)). People living in the provinces of the Roman Empire were often too poor to be able to afford slaves, so slavery was far less common than in Italy, and therefore the average household size was lower, likely to close to 4.5 to 5 inhabitants, which yields 12-15 square meters of residential space per capita, less than half of the level we estimated for Italy and about four times lower than per capita residential space estimated for Late Classical Greece.

Earning standards

The denarius was the standard monetary unit in the Roman empire, it was a silver coin that weighed 3.41 grams in 79 AD, and had 94% purity, thus in silver terms, unskilled workers in Pompeii typically earned half of a denarius per day (Vagi (1999)), or ca. 1.7 grams of silver per day, which appears to be representative of incomes for unskilled laborers in the prosperous parts of the Roman world. While thanks to the dry climate of Egypt, we have far more wage and price level data there than anywhere else in the Roman Empire, allowing us to know their real wages with a high degree of precision: In Egypt, standard pay in silver terms was 25% to 30% of a denarius per day, or 0.85 to 1 gram of silver per day, around 50 to 60% of the silver wages in Pompeii.

For comparison, in Classical Athens, the standard monetary unit was the attic drachma, a silver coin of 4.31 grams. Ober (2015) mentions that unskilled daily wages in 4th century BC Athens were 1.5 attic drachmas or 6.5 grams of silver, nearly four times the typical unskilled wages in Roman Pompeii and around seven times the silver wages in Roman Egypt.

Scheidel (2019) also noted as well that Greek soldiers were paid 3 to 6 times the rate of Roman soldiers in terms of silver during the time Rome was conquering the Greeks in the 2nd century BC. A slightly smaller degree of discrepancy emerges if you compare pay rates in the Roman army in the 1st century AD with pay rates in Late Classical Greece. In the 2nd century BC Roman soldiers made 100 denarii per year, the denarius weighed 3.9 grams at the time, so soldiers made 390 grams of silver per year. By the 1st century AD, as the Roman soldiers were professional volunteers and were better paid than a couple of centuries earlier: they made between 640 and 760 grams of silver per year. But, in Alexander’s army in the late 4th century BC, soldiers were paid 40 attic drachmas per month, which amounts to 2,070 grams of silver per year.

I should also note that Alexander’s army pay appears to have been very similar levels to Athenian military pay, which suggests Athenian wages were representative of the Greek world as a whole, or at least for the Aegean region. Greek rates of military pay in the early 2nd century BC also appear to be the same over a century earlier, at 40 drachmas per month.

In terms of basic consumer goods, such as wheat, instead of silver, the evidence points in the same direction: In well-documented Classical Athens, Athenian laborers in the 4th century BC made 13 to 16 liter of wheat a day (Ober (2015)). In Roman Egypt, unskilled wages were around 4 to 5 liters of wheat per day in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD (Harper (2017)), while rural wages in 18th century Britain were equivalent to 6.5 liters of wheat per day (Clark (2007)). As Classical Athens imported 80% of its grain, however, grain prices were likely higher in terms of consumption than in Egypt and 18th century Britain, thus these measures underestimated real wages in Classical Greece.

In Pompeii, we lack good price data for wheat, but it appears that the price of wheat was perhaps around 0.3 grams of silver per liter, which means wages there were about 5 to 6 liters of wheat per day, a similar level to rural wages in Roman Egypt and 18th century Britain, and around 35 to 40% of Athenian levels. However, Roman Italy was also a net grain importer, so grain prices were likely higher relative to other consumer goods in Italy compared to Egypt.

A curious fact: The conversion ratio of silver-to-gold in the late 4th century BC was 12.5 to 1. Thus, in terms of gold, unskilled Athenian workers working 275 days per year made 143 grams of gold per year or nearly 9,000 dollars: in terms of gold, those are higher unskilled wages than in most of the world today.

Demographics

From several sources, we can estimate the evolution of the total population of Europe, North Africa, and Western Asia (which we call “Western Eurasia”), which tripled from the 8th century BC to the early 1st millennium, then declined in Late Antiquity:

In Western Eurasia as a whole, population densities appear to have peaked in the Early Roman period, a time when Rome governed 80% of the Western Eurasian population: Schieldel (2019) notes that in the Western European provinces of the Roman Empire population densities were not reached again in the 14th century while in their North African and West Asian provinces, population densities did not surpass the Roman levels until the second half of the 20th century.

However, in certain regions, population densities peaked centuries before the Roman period. In fact, the Classical Greek population densities in certain regions were never attained again, not even today: the region of Boeotia in Central Greece had 25,000 inhabitants in medieval times, 40,000 inhabitants in the late 19th century, and today has 118,000 inhabitants. In Classical Greece, however, Boeotia had a population estimated to be between 165,000 and 250,000 inhabitants (Hansen (2006)).

Karambinis (2018) shows that in Mainland Greece (named in the Roman period as the province of Achaea), both the number of attested cities and the inhabited areas of these cities measured by archeologists declined by roughly 50% from the Late Classical period to the Early Roman Imperial period.

However, if the population of Boeotia declined by 50% to around 90,000 to 120,000, it was still several times more densely populated than in the Middle Ages. Thus, Greece likely was still much more densely populated in the Roman period than in the Middle Ages.

Intellectual output

Cultural and scientific production tends to be highly correlated with economic prosperity: Periods of cultural/scientific efflorescence tend to be highly correlated with economic prosperity. It is not a mere coincidence that the US has been the largest cultural, scientific, and economic power in the world for the past century. Whereas military power tends to be less correlated with economic prosperity: Russia today, the Soviet Union in the second half of the 20th century, and pre-modern military powers like the Mongols under Ghengis Khan, or Ancient Sparta, were not prosperous.

To have people like Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Euclid, Eratosthenes, and Archimedes (all of who worked during the 5th to the 3rd centuries BC) you need to have a flourishing intellectual environment with many people engaged in intellectual life, which is strongly correlated with economic prosperity. So we consider the inventory of known ancient philosophers from Western Eurasia from Curnow (2006) (who often tended also to be mathematicians, physicians, and scientists). He documents 2,300 ancient philosophers who lived from 800 BC to 640 AD.

If we divide the number of known philosophers by the estimated populations of Western Eurasia, we get the graph below. It suggests a peak in the density of philosophers in the population from 500 BC to 200 BC. It also shows a substantial decline from 200 BC to 200 AD, the time in which the Roman Empire was formed and consolidated, followed by an even greater decline with the near total collapse of the Roman Empire from the 4th century to the 7th century:

This data is consistent with the hypothesis that intellectual progress in antiquity peaked from 500 BC to 200 BC: most known philosophical and scientific advances before the 16th century occurred in this relatively short period, while intellectual and scientific activity was smaller in later centuries and collapsed by the Early Middle Ages.

Conclusion: the economic trajectory of the ancient world

Bringing together all this evidence, we can write down a narrative of the economic trajectory of the ancient world: As a result of intensive political competition and experimentation among over a thousand sovereign city-states, political institutions developed to an impressive degree. For example, the level of democratic participation in many Ancient Greek states was only attained again anywhere else in the world by the developed countries in the late 19th and 20th centuries. In fact, it has been argued by Bergh and Lyttkens (2014) that the inhabitants of Classical Athens enjoyed a high level of economic freedom.

As a result of these institutional developments combined with geography that facilitates sea trade, the Aegean and the regions that were first colonized by the Greeks achieved an impressive economic development from the 9th century BC to the 4th century BC, a period in which their population density increased by over an order of magnitude, reaching a peak of 8 to 10 million people living in Greece proper and its hundreds of overseas colonies by the late 4th century BC. The archeological evidence shows that living standards improved dramatically: the size and quality of houses and the consumption of durable household goods both increased by nearly an order of magnitude. This civilization achieved living standards during the peak of its efflorescence around 300 BC (this peak was also noted by Ober (2015)) that were perhaps not matched by any other pre-modern culture.

From 300 BC to the Roman period the prosperity of this region of the ancient world declined, but its institutions in watered-down form were exported to the rest of the Western Eurasian world (thanks in no small part to the Roman conquests of “barbarian” territories such as Western Europe), leading to the efflorescence of all the other provinces of the Roman Empire. Thus, aggregate economic activity in Western Eurasia as a whole likely peaked in the Early Roman period, while economic activity in the Greek core declined.

By Late Antiquity, however, all regions were declining and a dramatic collapse in living standards occurred all across Western Eurasia from the 2nd century to the 7th century. For example, Stephan (2013) shows that the median size of buildings identified as houses by archeologists in Britain declined by a factor of four and in Italy by a factor of three following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire.

The centralization of political power under Rome gradually progressed from the establishment of Roman hegemony in the early 2nd century BC, and this was a process that only ended in Late Antiquity: under the Early Roman period from the 2nd century BC to 2nd century AD, the Greek city-states still enjoyed some degree of autonomy in managing domestic affairs despite losing political sovereignty. Instead, the dissolution of the institution of the city-state was a very gradual process starting with the consolidation of Roman hegemony in the 2nd century BC but only ending with the centralization of Roman imperial administration in the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, when the concept of the Polis as a self-governing urban community was essentially dead. By late antiquity, the entire ancient world was ruled by a centralized autocratic regime, which is fundamentally incompatible with sustained economic prosperity. The gradual transformation of a rather sophisticated economic system to the Early Medieval standards of self-sufficiency was already assured by this institutional transformation.

It appears to be the case that the economic collapse of the civilization that was governed by the Roman Empire was ultimately caused by the formation of the Roman Empire. In other words, the Middle Ages were bound to happen as soon as Rome defeated Carthage in the Battle of Zama in 202 BC.

References

Bergh, A. and C. H. Lyttkens (2014), Measuring institutional quality in ancient Athens. Journal of Institutional Economics, vol. 10, pp. 279 - 310.

Clark, G. (2007), A Farewell to Alms. Princeton University Press.

Curnow, T. (2006), The Philosophers of the Ancient World: An A-Z Guide. Bristol Classical Press.

Hansen, M. H. and T. Nielsen (2005), Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis (Oxford).

Hansen, M. H. (2006), The Shotgun Method: The Demography of the Ancient Greek City State.

Hanson, J.W. (2016), An urban geography of the Roman world, 100 BC to AD 300. Archaeopress.

Harper, K. (2017), People, Plagues, and Prices in the Roman World: The Evidence from Egypt. Journal of Economic History, vol. 76, pp. 803-839.

Karambinis (2018), Urban Networks in the Roman Province of Achaia (Peloponnese, Central Greece, Epirus and Thessaly). Journal of Greek Archaeology vol. 3, pp. 269–339.

Kron (2015), Growth and decline. Forms of Growth. Estimating growth in the Greek World in E. Lo Cascio, A. Bresson, F. Velde (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Economies in the Classical World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Morris, I. (2004), Economic Growth in Ancient Greece. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, Vol. 160, pp. 709-742.

Ober, Josiah (2015), The Rise and Fall of Classical Greece.

Schiedel, W. (2019), Escape from Rome, Princeton University Press.

Stephan, R. P. (2013), House size and economic growth: Regional Trajectories in the Roman World, Ph.D. Dissertation at Stanford University.

Temin, Peter (2006), The Economy of the Early Roman Empire. Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 20, pp. 133-151.

Vagi, David (1999), Coinage and History of the Roman Empire. Sidney.

This is the best explanation I have ever seen for why the giant Roman Empire had such a surprisingly weak cultural and intellectual legacy compared to classical Greece.

I'm not sure I buy your analysis.

I don't think it makes sense to argue that a state of perpetual warfare and limited interstate commerce is a better situation than having a broad general peace maintained by a relatively small military base. That militarization was expensive. The need to buy military gear could bankrupt a Greek citizen of modest means.

The Romans imposed common laws for commerce, marriage and residence, so it was much more open to interstate trade. Piracy was much more of a problem before Rome made a point of suppressing it. The goal of most Greek cities was self sufficiency, but there are sound arguments that trade can improve living standards, and the Romans opened the door to much more widespread trade.

I seriously doubt that the typical ancient Greek family had 2.5-3 children and that only half of all households had as much as one slave. I also doubt that two adults were the norm. This sounds a lot more like the post-war US suburbs - ignoring the slaves - except that the suburbs were full of much larger families. Those numbers are way low for any traditional society.

I also think the slave count in pre-Roman Greece is way low. A lot of that constant warfare was looting and slave raiding, something much less common in the Roman era. Does that estimate include public slaves like the 400+ Scythian police and soldiers Herodotus noted? How many other public slaves were there? Does it include slaves tied to businesses who generally slept on site? One would expect a power law distribution of slave ownership with large numbers of slaves being rare but dominating the count in the aggregate. How were the prostitutes counted? They weren't necessarily slaves, but they were often treated like them.

Besides, what kind of metric is square footage per person? Are people in New York City or Singapore that much poorer than people in Sioux Falls or Kansas City just because they have smaller houses? As a former New Yorker, I would expect Roman apartments to be rather cramped for the most part, at least by suburban US standards, but there was a payoff for being able to live in Rome.

P.S. The Roman countryside was full of slaves. Maybe most rural citizens couldn't afford any, but the wealthy would own large farms with hundreds of slaves. This was true not just in what is now Italy, but in Spain, Gaul and elsewhere in the empire. Look up latifunda.