Ancient scientists and the economic performance of antiquity

Ancient economic history can be summarized by: Fast growth from 800 BC to 300 BC, slow growth from 300 BC to around 1 AD, negative growth from 1 AD to the 7-8th centuries AD.

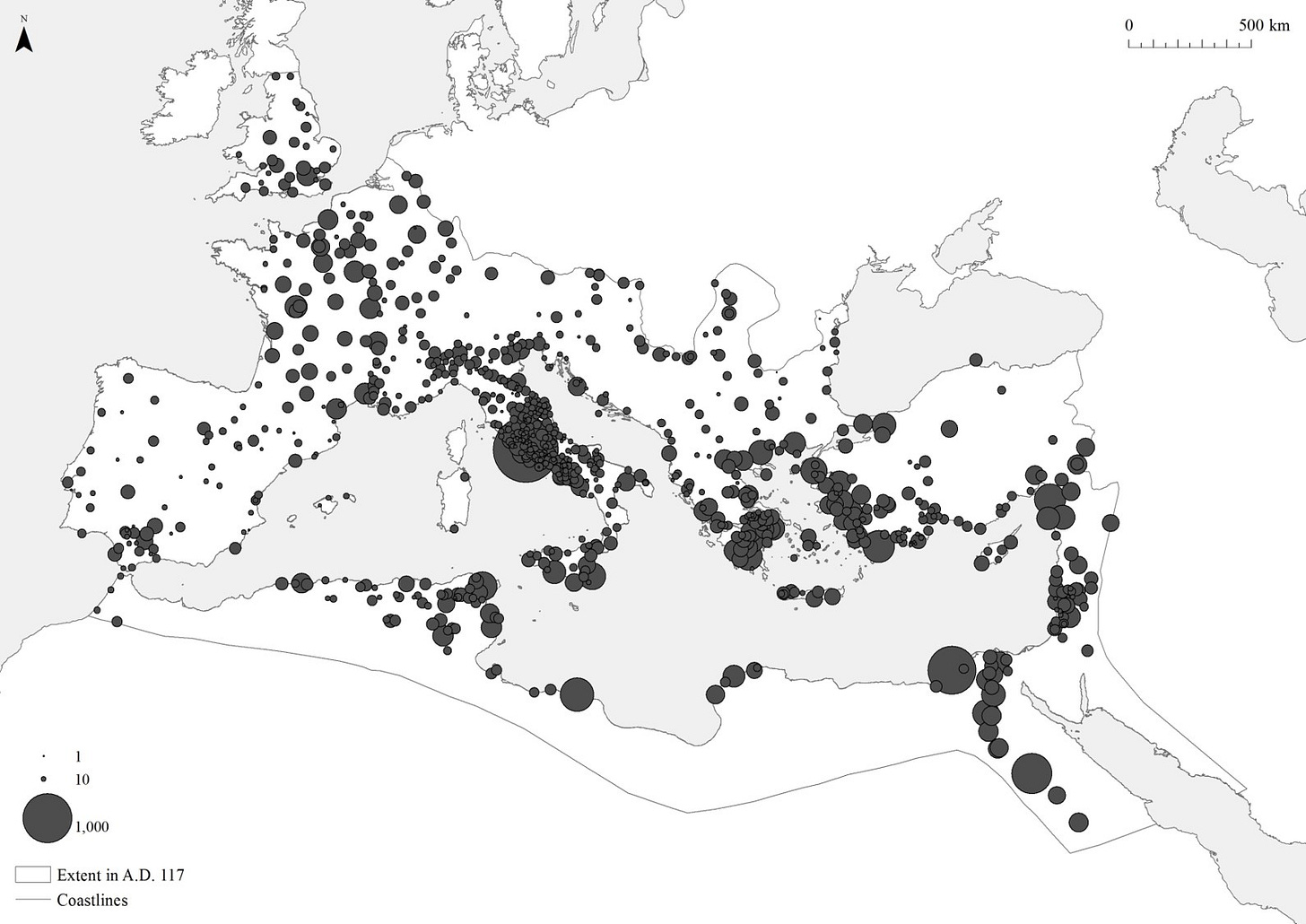

In this piece, I said that the Ancient Greek world was wealthier than the Roman Empire. This can give the reader impression that these two were distinctly separate worlds that existed in different periods. However, the reality is that the “Ancient World” was basically a network of city-states around the Mediterranean sea that flourished from the 1st millennium BC to the first few centuries AD; the majority of these cities were of Greek cultural background (over 1,000 Greek city-states are documented by the mid-4th century BC), but there were many non-Greek cities like Carthage and Rome. It just happened that Rome became the hegemonic city-state, and after centuries of hegemony, Rome formally annexed nearly all lands of the ancient world and centralized all the institutions of the State into itself. This process took several centuries: Rome achieved hegemony in the early 2nd century BC, but the Roman Empire could only be considered a centralized territorial state, like a modern nation-state, in the early 4th century AD, after Diocletian’s reforms which dramatically expanded the bureaucracy of the central authority. This was a very gradual transformation that was not perceived by people living at the time.

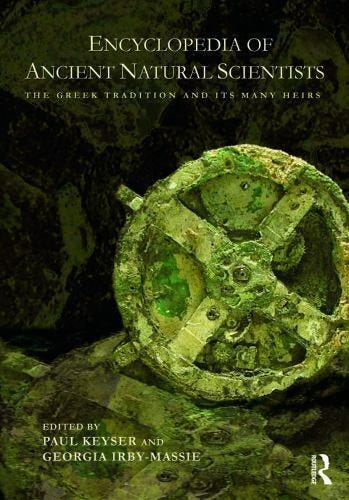

One of the most interesting datasets that measure the rise and fall of Greco-Roman civilization is the inventory of ancient scientists from the Encyclopedia of Ancient Natural Scientists:

This encyclopedia documents over 2,000 known ancient authors who wrote something that can be classified as science. The editors were liberal in assembling in including many authors to reach an inventory of 2,000 “scientists.” For example, Homer is included as the earliest entry in the inventory because the Illiad was regarded as a source of geographical information, and geography is a science. Out of these 2,000 authors, the overwhelming majority (about 90%) were Greeks, but there was a substantial minority of Romans (the authors with Latin names), and a few entries were Persians and Indians (which were included because they cited Greeks), and out of these two thousand, there was only one author from a remote island at the end of the inhabited world called Britain.

The trajectory of antiquity

If you take the authors that we have reasonable information about the time they were active and plot them over the centuries, you get the following graph of the distribution from 715 BC to 650 AD of how many ancient scientists were active over partitions of 105 years:

There is an exponential rise in documented ancient scientists from 8th century BC to 300 BC, just the time when Ancient Greek civilization had its dramatic economic development (as documented by the fact that the sizes of the ground-floor plans of typical Greek houses found by archeologists increased by about five times over this period). Then there was still moderate growth from 300 BC to the reign of the first Roman emperor, Augustus (31 BC to 14 AD). Then it was all downhill from the 1st century AD onwards (with the fastest decline from 125 AD to 230 AD, just before the Crisis of the 3rd Century). By the mid-7th century, Greco-Roman civilization was pretty much dead (note that the scientists documented up to 650 AD corresponds to the 105-year period from 545 to 650 AD). After that point, there are only records of a few Byzantine scientists from the late 7th century to the 9th century that we know existed because they were cited in some medieval Arab sources.

An interesting comparison can be made with the distribution of Mediterranean shipwrecks identified by archeologists from 2500 BC to 1500 AD is described by the following graph:

If we plot these two distributions together (identified scientists and shipwrecks per century), we get the following graph (they match well even in absolute numbers since we have 1,900 scientists and 1,500 shipwrecks reliably dated from 800 BC to 800 AD from each of the inventories):

The two datasets are very strongly correlated, which shows how scientific production and economic activity are correlated. However, the number of scientists rose 200 years before the shipwrecks. Why is that so? The shipwreck data is mostly restricted to shipwrecks in the Western Mediterranean which were intensively surveyed because it is next to Western Europe (the shipwreck graph is based on Parker's 1992 inventory of shipwrecks, and he says that his inventory of Mediterranean shipwrecks only records 80 ships from the 1,000 shipwrecks that were recorded by Greece’s department of Underwater Antiquities at the time). In antiquity, the Western Mediterranean region developed later than the Eastern Mediterranean, as shown by the fact that scientists with Latin names only began to show in large numbers in the Encyclopedia in the 1st century BC. Thus, the inventory of scientists is perhaps a more accurate indicator of the aggregate intensity of economic activity in antiquity than the inventory of shipwrecks.

Even during the period of peak Roman power and influence, roughly from 100 BC to 150 AD, the vast majority of scientists had Greek names; that is because the majority of the major cities of the Roman Empire were Greek-speaking cities in the Eastern Mediterranean: the fifteen largest cities at the time among cities with estimated geographical size were Rome, Alexandria, Antioch, Carthage, Ephesus, Rhodes, Corinth, Athens, Apamea, Pergamum, Syracuse, Cyrene, Sparta, Alexandria Troas, and Lepcis Magna. Of these 15 cities, only three were in the Western Mediterranean (Rome, Syracuse, and Carthage), and 12 out of these 15 cities were culturally Greek. Interestingly, it appears that the only major city of the Roman Empire in continental Western Europe was Rome.

Why growth slowed down after 300 BC?

There was a slowdown in the growth rate of documented scientists from 300 BC onwards, as well as a lack of major breakthroughs after the dramatic achievements by the 3rd century BC, one interesting question is to explain what caused this apparent slowdown of growth in scientific output in the ancient world after 300 BC (with an associated slowdown in the growth in economic activity). Demographic transition to a regime of low fertility and low population growth might be a major factor: by 350 BC, the combined population of Greek speakers across the ca. 1,000 documented city-states was estimated at around 8 to 10 million; it did not increase much in later centuries, as Hanson (2006) estimated that the total number of Ancient Greek city-states that have existed totaled “only” around 1,500, and only a fraction of those was founded after 350 BC. Written sources claim that fertility rates and population densities in the Greek homeland had already declined by the mid-2nd century BC:

“In our own time the whole of Greece has been subject to a low birth rate and a general decrease of the population, owing to which cities have become deserted and the land has ceased to yield fruit, although there have neither been continuous wars nor epidemics... For as men had fallen into such a state of pretentiousness, avarice, and indolence that they did not wish to marry, or if they married to rear the children born to them, or at most as a rule but one or two of them, so as to leave these in affluence and bring them up to waste their substance….”

― Polybius, The Histories, Vol 6: Bks.XXVIII-XXXIX

Another reason is that perhaps most of the low-hanging fruits were picked up by 300 BC, given the magnitude of technological possibilities of the ancient world. They were a civilization whose technological possibility frontier was restricted to the knowledge creation capacity of around 10 million people in 300 BC. While declining in the older cities of Greece proper, the population still grew after 300 BC in the aggregate Mediterranean world. Considering that the population of scientists roughly doubled over the period from 300 BC to 1 AD, the total knowledge-producing population increased to perhaps around 20 million people by the time of Augustus, which was likely the population of all the Mediterranean city-states plus their hinterlands.

Thus, in Roman times, the “civilized population” was likely much smaller than the total population inside the Roman territorial dominion, which explains why the “average Roman” living standards were lower than the “average Greek,” as I argued before. Just like the industrialized population of the British Empire in the early 20th century was much smaller than its total population. Thus, the degree of economic and technological complexity achieved in a city like Herculaneum was perhaps close to the frontier of possibilities, given the demographic scale of their civilization.

Why did Greco-Roman civilization ultimately collapse after the first century AD?

To explain the collapse of this civilization is comparatively easy. As the political centralization under Rome consolidated, the civic-institutional framework of the city-states that supported this civilization gradually dissolved.

What you say is definitely true and there was a general cultural decline after the augustan era, but there is also a paucity of surviving texts from the later periods which creates a survivor bias.

For example we know that there were many writings about the roman conquest of Dacia, including books by emperors Trajan and Hadrian, but most historical works that mention this event did not survive.

It is possible that later copyists where simply less interested in the imperial period and did not invest in the effort of copying books written in that period thus obscuring from our knowledge potentially significant "scientists" of the principate.

Since Gibbon there has been this idea that the decline of the ancient world started with Commodus or maybe with the Antonine Plague so I find it intriguing your arguments that the decline started earlier.

Maybe Pax Romana itself was a culprit? With wars being fought only near distant frontiers there was less need for military innovation and with political life being reduced to intrigues at the imperial court there was less need for the elite to patronize culture and "science" to gain prestige.