The Malthusian Trap Never Existed

Pre-modern economic performance as documented by urbanization trends

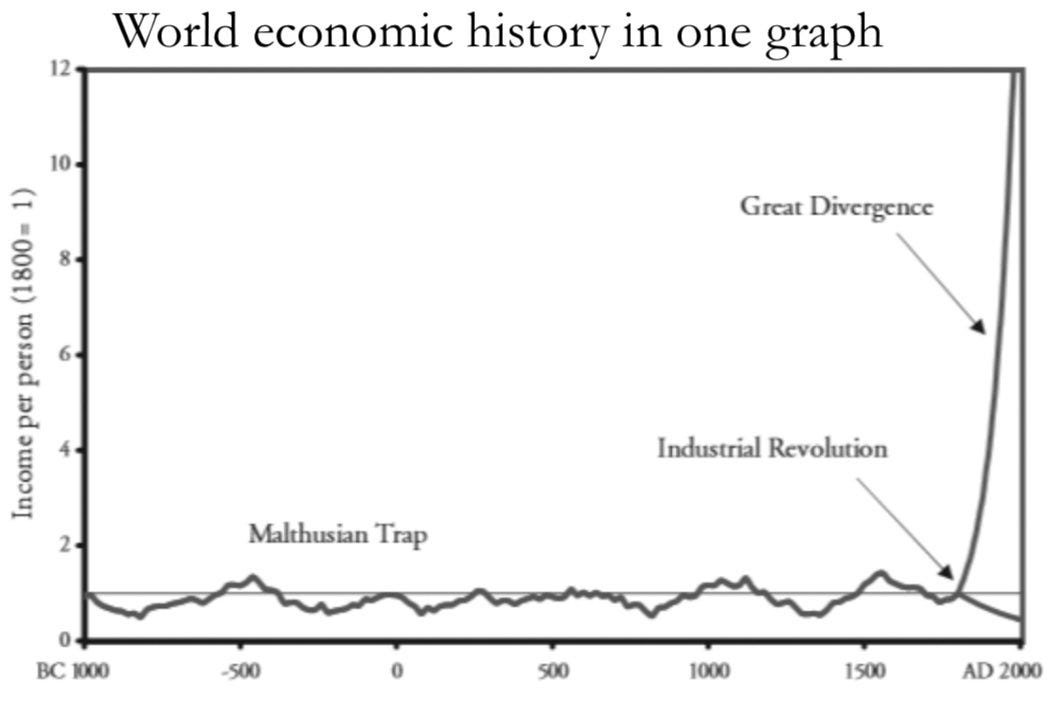

Economists often assume that there was no economic growth before the late 18th-century takeoff of modern economic growth. For example, this graph is typically used as a quick description of world economic history. This conceptualization is boring if one is interested in pre-modern history as it suggests that nothing very interesting in economic terms happened between the invention of writing and the industrial revolution:

The model behind this graph is the so-called Malthusian model. It can be stated as follows: There exists a level of income that is valid for all times and cultures defined as the “subsistence level.” The model assumes that population increases when incomes are above this level and decreases when incomes are below this level. Then, if incomes are above the subsistence level, as population increases, the capital to labor ratio tends to decrease, decreasing incomes back to the “subsistence level.” Analogously, if incomes are below the subsistence level, the population would tend to decrease, increasing the capital to labor ratio and increasing incomes toward the “subsistence level.” It was only when technological progress became fast enough to make incomes grow faster than the population could grow that humanity escaped the Malthusian trap.

While it is true that the modern growth explosion that occurred since the late-18th century has made pre-modern economic performance appear rather unimpressive, I do have some serious reservations regarding the Malthusian trap thesis. Instead, the patterns that I perceive appear to be better described by a model where: Economic growth existed in pre-modern times but was much slower, and there were also periods of sustained economic shrinkage.

First is the fact that several episodes of economic growth before the late 18th century are documented by archaeologists and historians, and second that the claims of long-term stagnation are mainly based on real wage time series for Britain computed by Gregory Clark that have low accuracy and are not really representative of historical economic conditions. It would be an interesting exercise to attempt to measure how vast pre-modern economic growth was compared to modern growth.

Real wages are identical to the marginal product of labor if we have a perfectly competitive labor market. Then, we can use the real wage time series index to measure the evolution of labor productivity if the sample of wage rates we use to construct the index is representative of the working population of the economy. In a highly sophisticated market economy like the 21st century US or Western Europe, average wages might be a very good proxy for labor productivity. But, was the sample of wage rates used by Clark representative of the working population of Britain over the nearly thousand years that spans the index? I would be very surprised if it was. Also, how can one believe that the British labor market was operating under conditions that approximated perfect competition during the middle ages?

Instead of using wages data, which is valuable data but tends to be extremely noisy to capture long-term trends for pre-modern economies, one might be tempted to use estimates of urbanization rates. Historically, urbanization rates were closely correlated to the degree of economic development. This correlation occurred for various reasons:

As incomes increase, people spend a lower fraction of their income on food and a higher fraction on manufactured goods and services. As food is produced by agricultural activity, which is primarily performed by the rural population, the fraction of the population living in rural areas tends to decrease.

As the degree of division of labor in society increases, the proportion of the population engaged in the direct harvesting of natural resources in primary activities (agriculture, fishing, hunting, mining, etc.) declines, and a higher proportion of the working population engages in processing and service activities. Living in cities is naturally suited for economic activities that do not require the worker to work the land, as individuals can more easily meet others and create networks in urban areas.

Empirically, it appears historical reconstructions of national accounts for economies where we have good data are very strongly correlated with urbanization rates:

As I show below, the urbanization data suggests, instead of a Malthusian trap scenario where income levels fluctuate around a hypothetical “subsistence level,” instead, since Ancient Greece up to the 19th century, there were periods of sustained economic development in European history, and there were also periods of sustained economic regression across the continent as well.

A short history of european urbanism since the early 1st millennium BC

I only consider the population living in towns over 5,000 inhabitants as urban to serve as a common standard of the rate of urbanization across long periods of time. The first urban agglomerations with over 5,000 inhabitants in Europe emerged in Ancient Greece. In the period known as the Greek Dark Age from 1000 BC to 750 BC, Morris (2005) estimates the largest towns likely had around a few thousand inhabitants. Thus, the total urban population of Europe at the first couple of centuries of the first millennium BC was zero according to our criteria.

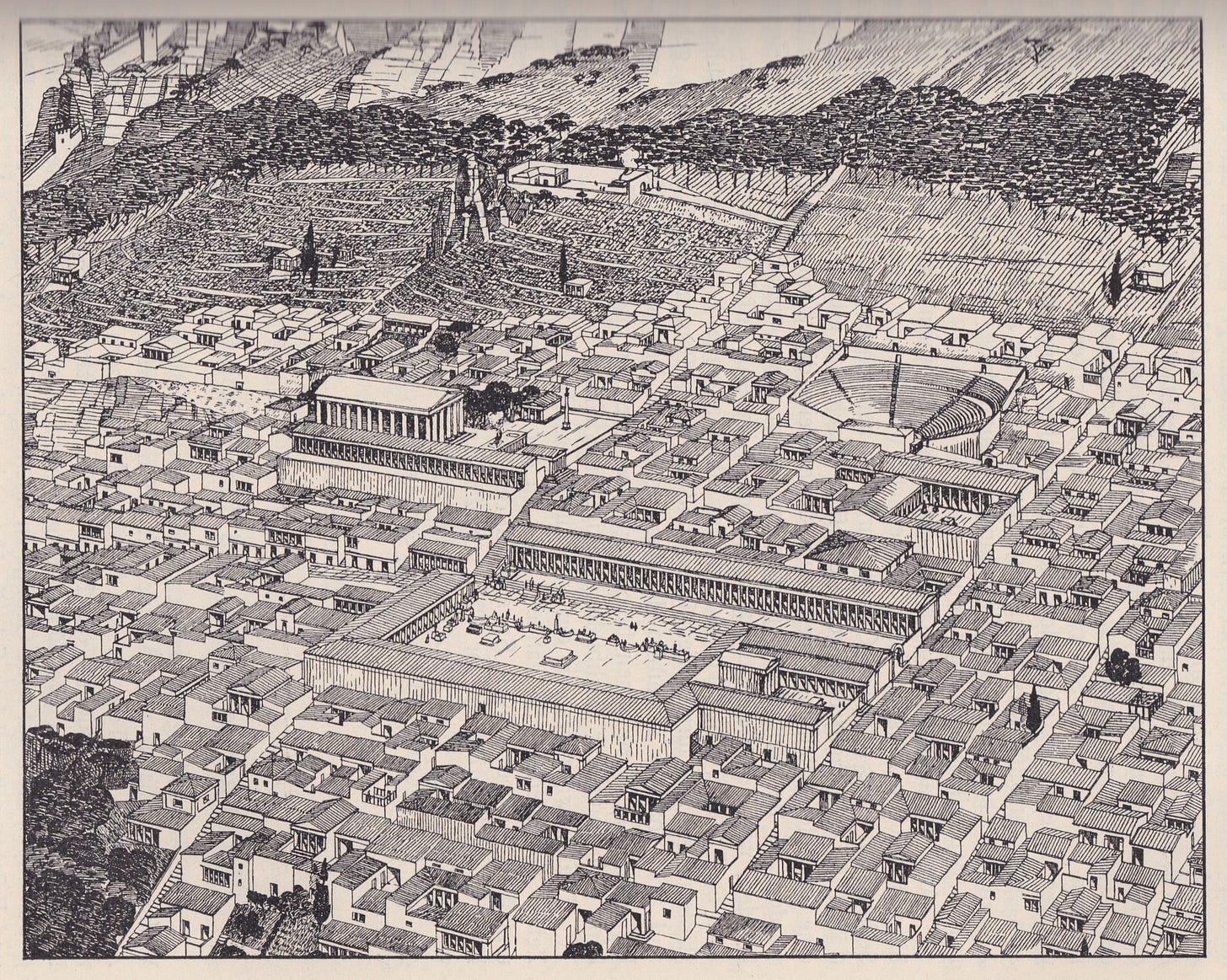

The efflorescence of Ancient Greek civilization occurred over the next half of millennium, and by the late 4th century BC, around the time of the death of Alexander the Great and Aristotle, Ancient Greek civilization attained its demographic peak: There were over a thousand sovereign city-states with a combined population estimated at around 8 to 10 million. From the 9th century BC to the 4th century BC, population density in Greece increased from 3-4 inhabitants per square kilometer (Morris (2004)) to 40-45 inhabitants (Ober (2015)), while the territory settled by the Greeks greatly expanded.

By that point in time, using the Polis inventory dataset of 1,035 Greek city-states, Ober (2015) estimates that between 2.5 to 3.0 million Greeks lived in towns over 5,000 inhabitants. This dataset also implies that there were around 200 Greek towns over 5,000 inhabitants and about 100 Greek cities over 10,000 inhabitants by the late 4th century BC. Ober also estimates that 75% of the population of the Ancient Greek world resided in Europe, so the urban population of Greeks in Europe circa 300 BC was 1.9 to 2.3 million.

Some additional factors have to be taken into consideration to estimate Europe’s urban population by the end of the 4th century BC: The Greeks were not the only urbanized culture in Europe by that time, as other urbanized cultures were flourishing as well: Etruscans and the Latins in Italy. There were 150 city-states in peninsular Italy at the time which soon formed an alliance that constituted the future core of the Roman Empire (Scheidel (2019)). In addition, there were dozens of non-Greek city-states in Iberia, Sicily, Corsica, and Sardinia, and archeologists estimate that even north of the Alps, by the late first millennium AD, a few Celtic towns reached 5,000 to 10,000 inhabitants. Overall, Europe’s urban population at ca. 300 BC might have been around 2.3-2.8 million, residing in 180 towns over 5,000 inhabitants.

Let us consider the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, during the Early Roman Empire. By that time, urban networks had spread beyond the Mediterranean basis, as the Romans founded hundreds of colonies north of the Alps, such as Paris, Cologne, London, and Munich. While the population of Greek cities had declined, in every other part of Europe, both urban and rural populations increased. For the Early Roman Imperial period, Hanson and Ortman (2017), based on the inventory in Hanson (2016) of 1,388 Roman cities, estimate that 14 million people lived in towns with over 5,000 inhabitants, and their dataset suggests there were around 700 to 800 towns over 5,000 inhabitants across the Roman Empire. Non-European cities constituted nearly 50% of the Roman urban population.

During the Early Roman Imperial period, the urban population of Europe reached a peak of 7 million people living in around 400 to 450 towns over 5,000 inhabitants (the Roman European cities were smaller on average than the much older cities in the Middle East), and around 1 million living in the city of Rome itself (Hanson and Ortman (2017) have a point estimate of 923,000). During late antiquity, by the mid to late 4th century, the urban population of Europe declined substantially, to slightly less than 4 million (this estimate is of lower quality, as it is based on Chandler's (1987) somewhat outdated demographics estimates, he estimated the number of cities over 40,000 inhabitants and the statistical regularity regarding this number with the total urban population. However, an interpolation produces almost the same exact figure).

Following the decline and near-total collapse of the Roman Empire, from the 2nd century to the 7th century, there was a near-total collapse in European urbanism. By the 7th century, the number of towns in Europe declined to only around 30 to 40 towns with over 5,000 inhabitants (Buringh (2021)), from a peak of over 400 towns five centuries earlier. This cataclysmic collapse of the Western Eurasian urban system gave us the term "dark ages" to describe the early medieval period.

However, during the Middle Ages from the 8th to the 14th century, the number of towns over 5,000 as well as the aggregate urban population increased by over an order of magnitude, reaching nearly 6 million urbanites spread over 400 towns just before the black death. From the 14th century to the late 18th century, urban growth continued as the urban population of Europe increased from 6 to 18 million and the number of towns over 5,000 inhabitants increased from 400 to 1,100 towns. Europe's largest city, London, was approaching 900,000 inhabitants, comparable to Rome's size during the peak of Roman power.

From the datasets of Buringh (2021), and Bairoch and Goertz (1986), I estimated Europe's urban population from the late-18th century to 1950. The impact of modern economic growth is very apparent, as the urban population living in towns over 5,000 inhabitants increased from 18 million to 250 million, while the total population of Europe barely doubled over the same period.

The trajectory of European urbanization rates and the trajectory of economic growth

Incorporating all this data (Buringh alone (2021) estimates city-size for 2263 european cities for 100-year interval from 700 to 2000), interpolating the urban population estimates, and dividing by the estimated population of Europe over the past 3,000 years we get the following graph below, which describes europe’s rate of urbanization from the early 1st millennium BC to 1950:

This graph suggests a much more nuanced and interesting trajectory of macroeconomic performance for Europe than the Malthusian-trap model. While it is clear that the urbanization rate increased at much faster rates from the late 18th century to 1950, the graph truly shows graphically how much faster modern economic growth was to previous episodes. It also shows that there was slow progress upwards from the 8th century to the 18th century, roughly at 10% of the urbanization growth rate in the 19th and 20th centuries. The decline and fall of the Roman Empire from the 2nd century to the 7th century is also clear. The empirical evidence from archeology also suggests that it was likely the greatest sustained process of economic regression in human history. Also, the economic flourishing of Classical Greece and other parts of the European Mediterranean from the 9th to the 4th century BC appear to have constituted the fastest period of economic growth in Europe until the late-18th century.

This data shows that is no evidence of any tendency for the rate of urbanization to stabilize around a level consistent with the Malthusian model’s “subsistence level.” Instead, the urbanization rate suggests that over the last three millennia of the history of Europe, there were long and sustained periods of economic progress and regression and that modern economic growth has been a dramatic acceleration compared to the pre-modern trend, instead of a complete break from it.

These datasets suggest that the urbanization peak during the Roman period in the early 2nd century was only surpassed in the 19th century. As this is the European average, we include the population of less urbanized parts of Europe. If we consider only the Ancient Greek world at around 300 BC, their rate of urbanization appears to have reached 30-35% of their population, comparable to the rate of urbanization of Europe as a whole in the early 20th century. This piece of empirical evidence suggests that the world’s economic history might hold much more exciting discoveries than the predictions of the Malthusian-trap model.

References

Bairoch, Paul and Goertz, Gary (1986), Factors of Urbanisation in the Nineteenth Century Developed Countries: A Descriptive and Econometric Analysis

Buringh, Eltjo (2021), The Population of European Cities from 700 to 2000: Social and Economic History

Chandler (1987), Four Thousand Years of Urban Growth

Hanson, J.W. and Ortman (2017), A Systematic Method for Estimating Greek and Roman Urban Populations

Hanson, J.W. (2016), An urban geography of the Roman world, 100 BC to AD 300

Ober, Josiah (2015), Rise and Fall of Classical Greece

Morris, Ian (2005), The Growth of Greek Cities in the 1st Millennium BC

Mogens Herman Hansen (2006), The Shotgun Method: The Demography of the Ancient Greek City State

Scheidel, Walter (2019), Escape from Rome

In Hackett-Fisher's The Great Wave, he notes that European material historians had long noted a cycle, perhaps 150-200 years long, of price stability and instability. Price stability is generally correlated with political stability, but there may be a Malthusian component since prices do not rise in unison. Prices for land rent, food and fuel tend to rise during periods of instability while prices of manufactured goods fall. Some historians argue that this is part of a population cycle. Turchin takes it further arguing that the thing to watch is the population of the elite with respect to available resources. One is more likely to have wars and associated plagues culling the population pressure than outright dying. I consider it an excellent crackpot theory which doesn't mean it is completely wrong.

If nothing else, you can see a slow ratcheting up of European productivity. The Dark Ages gave us things like chimneys, cheaper iron, better plows - originally developed in China and better ways to harness horses. Smil goes into this in some depth from a technologist's viewpoint. Greece did very well as a salt water power. Rome took its civilization inland. The Dark Ages created a civilization for the heavy wood forests of Northern Europe.

Economists tend to oversimplify matters historical. If that's the Malthusian trap, then it's simplistic.

Interesting post - that urbanisation graph is remarkable!

I haven't tried to follow through the implications for your argument, but it's worth noting that the Malthusian trap you refer to here isn't the one that Clark models in Farewell To Alms. He argues that most historic cultures operated at well above subsistence level, and finds his Malthusian equilibrium at the intersection of culture-specific birth rate and death rate curves.