The Great Convergence

"The Great Divergence" gets it backwards: Different civilizations which never had convergent trajectories have converged in recent centuries

Introduction

Our world today has been completely and radically transformed by a historical process that began in Northwestern Europe and in North America around the turn of the 19th century. Today economists call this phenomenon the “beginning of modern economic growth,” although the term “Industrial Revolution” was more popular a few decades ago. The enormous impact of modern economic growth on our world can easily be noted in the growth of the global population from 1 billion to 8 billion over the last two centuries.

The piece I wrote on “Escape From Rome” focuses on this topic from the perspective of one book that seeks to contribute to an explanation for this extremely dramatic phenomenon. The famous book “The Great Divergence” by David Pomeranz also engages with this question from a global historical perspective. This book is extremely famous, and his thesis even has its own Wikipedia page, yet, it appears to be the case that Pomeranz got things precisely backward.

The fact is that before modern times, the world consisted of distinct civilizations on divergent paths. It was only in recent centuries that intercontinental integration is inducing all these societies to converge in terms of institutions and technologies, which produced the strong tendencies for the convergence of living standards that we observe today all across the world.

The Great Divergence Hypothesis

Pomeranz seeks to explain why modern economic growth first started in the “West” (Western Europe and North America), but instead of focusing on changes in Western society that might have accelerated economic growth around 1800, he first argues that the 18th-century West was not different enough from the rest of the world at the time (or different in the right directions) to explain why the other parts did not achieve the same accelerated growth. Instead, he tries to explain the origin of modern economic growth in the West due to factors that were exogenous to the societies of the West. It is a similar argument to Morris (2010), as both authors think that European colonization of the Americans played an essential role. Although as Scheidel (2019) notes, the European act of colonizing the Americas was not something that could be taken as an exogenous shock to European society.

Half of Pomeranz's book consists of a narrative claiming that the richest parts of late 18th century Europe were not richer and perhaps poorer than the developed parts of the rest of Afroeurasia. He focuses on the comparison between China and Europe, claiming that if living standards in China were equal to or higher than in Europe, then we should not expect Europe to be more developed compared to the other parts of the Old World as well. His narrative consists of a series of anecdotes like “Chinese stoves were more heat efficient than European stoves,” it is not based at all on the careful use of statistically representative data. This is analogous to applying the following line of reasoning to claim that the living standards of the US are not higher than in Pakistan today:

(1) Farmers in both the US and Pakistan trade their crops for money, which shows that both countries have advanced monetized economies.

(2) There are banks in both US and Pakistan, proving their financial systems are similar.

(3) There are traffic jams in Karachi, which shows cars are common in Pakistan as they are in the US. Thus we conclude that Americans do not enjoy higher standards of motorized transportation than Pakistanis.

(4) Karachi, with 15 million inhabitants, is a larger city than New York, the logistics of supporting such a huge city suggest that Pakistan has more developed long-distance trade networks than the US.

(5) While Americans live in much larger houses, have much more infrastructure built of durable materials, their farms have more tractors, their factories have more installed motive power per worker, and Americans consume much more meat and dairy than Pakistanis we cannot say these differences reflect real differences in development instead of just cultural differences in lifestyle.

Therefore, (1)-(5) imply that we should conclude that living standards in Pakistan are equal to or higher than in the US in the present, and any measured difference in the future must be due to some “great divergence” induced by exogenous factors, not endogenous developments.

This kind of historical narrative takes me back to my undergraduate days: Being Brazilian I studied at a Brazilian university and I remember hearing a “theory” proposed by Brazilian academics that the “Industrial Revolution” was financed by the Brazilian gold that was stolen from us by Portugal. This “theory” was based on the following three facts: (1) Brazil experienced a gold rush in the 18th century. (2) Portugal taxed the output. (3) Portugal imported textiles from Britain. Therefore, the logic goes: Brazilian gold gave Portugal the money to create demand for the output of British textile mills, generating the industrial revolution. Pomeranz essentially articulates a version of this Brazilian theory of the industrial revolution but from a perspective shifted to the US. Instead of British industrialization being driven by demand created by Brazilian gold, it was cheap American cotton subsidized by slavery that reduced costs in the British textile mills, which set off the magic spark that summoned modernity.

One should note obvious issues with this theory: the European powers lost all their North and South American colonies during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and as the US was independent since the 1780s, there were no legal barriers preventing the textile industries located in the Yangtze-valley (the region in 18th-century China he claims was similar to Britain, down to the level of textile production per capita) from importing cheap American cotton and creating their own industrial revolution just as British industries did, indeed, today former European colonies like Brazil and Australia supply enormous amounts of natural resources to Chinese manufacturing.

The evidence also does not indicate that the coercive extraction of American resources by European colonial powers contributed to economic development. If the expansion of natural resource endowments available to Europeans were the magic spark of modern economic growth, then modern economic growth would have started 300 years earlier when large-scale colonization of the Americas began. In fact, 300 years of colonialism had the precisely opposite effect: the two countries that controlled 90% of the colonial population in the Americas, Spain and Portugal, were the poorest countries in Western Europe. It is not hard to understand why: by conquering most of the Americas, these two states managed to expand their tax base beyond Europe dramatically, and these additional resources fortified their pre-modern institutions against the pressure for institutional innovation caused by interstate competition in Europe.

Another issue is that the claim that slavery helped to jumpstart modern economic growth is in direct contradiction with basic economic theory: slaves do not own the marginal product of their labor which distorts incentives, leading to lower levels of efficiency. Instead, the emergence of modern economic growth was a time in which there was a large reduction in the use of coerced labor as both slavery and serfdom were things of the past in 19th-century Western Europe and after the US abolished slavery in the mid-19th century, economic growth did not slow down but continued at an even faster pace.

The rest of the Old World was not remotely behind Europe in terms of the use of coercion in their societies during the 17th and 18th centuries. In fact, nearly all pre-modern states were ruled by autocratic monarchies in which the King/Emperor was the State and God. All the population who were subjects of the King/Emperor were functionally the King/Emperor’s property: the monarch could execute anybody on a whim. For a contemporary example, look at North Korea for a textbook example of a typical pre-modern state. Slavery, as it was conceived in 19th century America or in Classical Greece, is an institution of societies that had first developed the concept of the free citizen as opposed to being a King’s subject. Then, the concept of slavery developed as the counterpart to citizenship, as its negation. Societies where a significant fraction of the population consists of free citizens are extremely rare in the pre-modern record: that was the case for only a few city-state cultures like Classical Greece and Renaissance Northern Italy.

Finally, the biggest issue of all is that these theories rest on a pseudo-scientific assumption that the “economy” of a society is some sort of engine that needs to experience a jumpstart to transition from a “pre-industrial” state to an “industrialized” state. That is fundamentally mistaken: there is an important concept in economics called diminishing returns. The less industrialized an economy is, the less capital there is and, therefore, the greater the return on investment, thus the easiest it is to grow, not the inverse: that is why in recent decades, countries like China, Thailand, Pakistan, and India have grown much faster than rich countries like the US and Germany. The fact that the fastest growing economies during the 19th century were also among the richest economies in 1800 implies there was an enormous potential for development over the entire world, which was finally potentialized in the 20th and 21st centuries.

A polycentric system or multiple systems?

An interesting claim that Pomeranz makes is that the world was not centered in Europe until a couple of centuries ago but that it was polycentric. However, in more precise terms, it is not true that the world was polycentric but that there were multiple worlds: Before modern times, each part of the world had a system of international relations that was isolated from the others to such an extreme degree that a major power in one of such systems did not exist geopolitically to the players in other systems. For example, when England was involved in the Hundred Years’ War in the 14th and 15th centuries, they did not take into consideration the diplomatic reaction from the emperor that ruled China at the time as China did not exist as a geopolitical player that could potentially interfere with the interests of the Kingdom of England. However, starting in the 16th century and over the next three centuries, these separate worlds gradually became parts of a single global system of international relations.

The Ancient Greek historian and political philosopher Polybius, writing in the mid-2nd century BC, already noticed something analogous was occurring during the centuries up to his time: the histories of Europe, (North) Africa, Italy, Sicily, Greece, and (Western) Asia were becoming increasingly interconnected. Polybius pointed out that events in the one landmass bordering the Mediterranean basin started to impact all the other lands close to the Mediterranean. In other words, there was a process of integration of the lands of the Western Eurasian hemisphere into a single system of international relations by the end of the 1st millennium BC. Then, after a quite long pause during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, starting in the 16th century, the parts of the world outside of this Western Eurasian ecumene became politically integrated with Western Eurasia, creating our modern “globalized” world.

Thus, at the turn of the 16th century there was no such thing as “the world”, instead there were at least six worlds that featured urbanized civilizations:

The Mesoamerican world, dominated by the Aztec Empire.

The Andean world, dominated by the Inca Empire.

The Western Eurasian world, which was the largest “world” by geographical extension, included all of Europe and was fragmented into many states, the largest being the Ottoman Empire.

The Southeast Asian world, fragmented into many states, although the Mughals unified most of the Indian subcontinent.

The Chinese world, which was dominated by a single state for most of its history.

The Japanese world, which was fragmented into many states during the Sengoku period and later unified during the Edo period.

There was some economic interaction between the major regions of the Old World thanks to long-distance trade routes for very high valued goods in proportion to their weight, like the famous silk road in Central Asia. China imported silver from Japan, as European communities imported spices from India. But the feasibility of carrying high-value goods like silver and spices across long distances did not mean it was feasible for armies to move across the same distances for a state to project military power.

That China and Japan were two separate worlds is a dramatic example of this historical reality. Despite the geographical proximity and substantial cultural similarities, they were two separate worlds due to a lack of geopolitical interaction. For example, during the Sengoku period, Japan was divided into many small states controlled by warlords, and as the King of England, each Japanese warlord was not worried about the position of the Chinese state regarding their rivals like they were not worried about the diplomatic positions of the Ottomans. After Japan was again unified in the following Edo period, thanks to its extreme isolation from other regions of the world, the samurai class managed to ban firearms. That is the only example of a society abandoning firearms in human history, which was only possible because pre-modern Japan was a self-contained geopolitical system: if there were external state-level competitors, Japan could not have done such a thing.

The Divergence that Never Was

As historical China and Europe existed as two separate worlds, their social, economic, and technological trajectories were dramatically different. When confronted with the quantitative data available, the claim made by Pomeranz that Europe and China have attained similar development and followed similar trajectories until the 18th century appears to be not only wrong but particularly misguided. Even if there were similarities at some point in time, there is no reason to believe that the whole trajectory should tend to be identical.

Let us compare the trajectories of Europe and China in urbanization rates, which are strongly correlated with income. The urbanization statistic for Europe is now modified so that the threshold for a town to count as “urban” is lowered to 2,000 inhabitants. I made it so to make the graph comparable with data estimated for China from 1100 to 1900, from Xu et al. (2018), which, unfortunately, is of very low quality.

While the data for Europe reflects a dramatic increase in economic growth after 1800, it also shows that there was a long upward trend across the whole of Europe for a thousand years up to 1800. Thus, this data suggests that modern economic growth was just a large acceleration of a broader positive growth trend in Europe that began in the Early Middle Ages, not a discontinuity with the previous centuries. While for China, the trajectory of urbanization rates suggests there was not any sustained trajectory of either increasing or decreasing prosperity for the 2nd millennium: China appears to have had periods of higher relative levels of prosperity like the 12th and 16th centuries and periods of lower prosperity like the 18th and 19th centuries.

These two trajectories are what one would expect from an international system of competitive states (Europe) versus a system monopolized by a single state (China): The monopolization of political institutions by a single autocratic state leads to a lack of institutional improvement which is inconsistent with sustained economic growth, while competition between states allows for improvement through experimentation and learning from the experience of other states.

Regarding Pomeranz’s claim that living standards in East Asia were equal to or higher than in Europe in the 18th century, note that our graph shows that by the late 18th century Europe’s urbanization rate was two and a half times China’s, which implies a similar discrepancy in per capita incomes. Data for wages and prices computed in studies such as Broadberry and Gupta (2006) also suggest that there was a large discrepancy in living standards at the time: daily wages for unskilled workers in the richest parts of China were 2kg of rice and in Toyko, Japan, they were 1.5kg of rice, for comparison, daily wages for rural laborers in Britain were 5kg of wheat and in the richest cities of Europe like Amsterdam, and London, wages reached 8kg to 10kg of wheat: In the richest parts of 18th century Europe incomes were already several times higher than anywhere in China and Japan.

Illustrating this quantitative comparison, Adam Smith in 1776 provides a rather vivid description of the standards of living in China from a European perspective:

The accounts of all travellers, inconsistent in many other respects, agree in the low wages of labour, and in the difficulty which a labourer finds in bringing up a family in China. If by digging the ground a whole day he can get what will purchase a small quantity of rice in the evening, he is contented. The condintion of artificers is, if possible, still worse. Instead of waiting indolently in their work-houses for the calls of their customers, as in Europe, they are continually running about the streets with the tools of their respective trades, offering their services, and, as it were, begging employment. The poverty of the lower ranks of people in China far surpasses that of the most beggarly nations in Europe. In the neighbourhood of Canton, many hundred, it is commonly said, many thousand families have no habitation on the land, but live constantly in little fishing-boats upon the rivers and canals. The subsistence which they find there is so scanty, that they are eager to fish up the nastiest garbage thrown overboard from any European ship. Any carrion, the carcase of a dead dog or cat, for example, though half putrid and stinking, is as welcome to them as the most wholesome food to the people of other countries. Marriage is encouraged in China, not by the profitableness of children, but by the liberty of destroying them. In all great towns, several are every night exposed in the street, or drowned like puppies in the water. (p. 64-65 of Smith, Wealth of Nations, Penn State Electronic Classic Series Publication).

What I find the most interesting about this account is that it shows that before the age of modern economic growth, living standards across the world were not uniform but could vary quite dramatically. In fact, living standards in China today, with its per capita GDP of 35% of British levels, appear to be similar relative to Britain’s as in the late 18th century.

So what caused modernity after all?

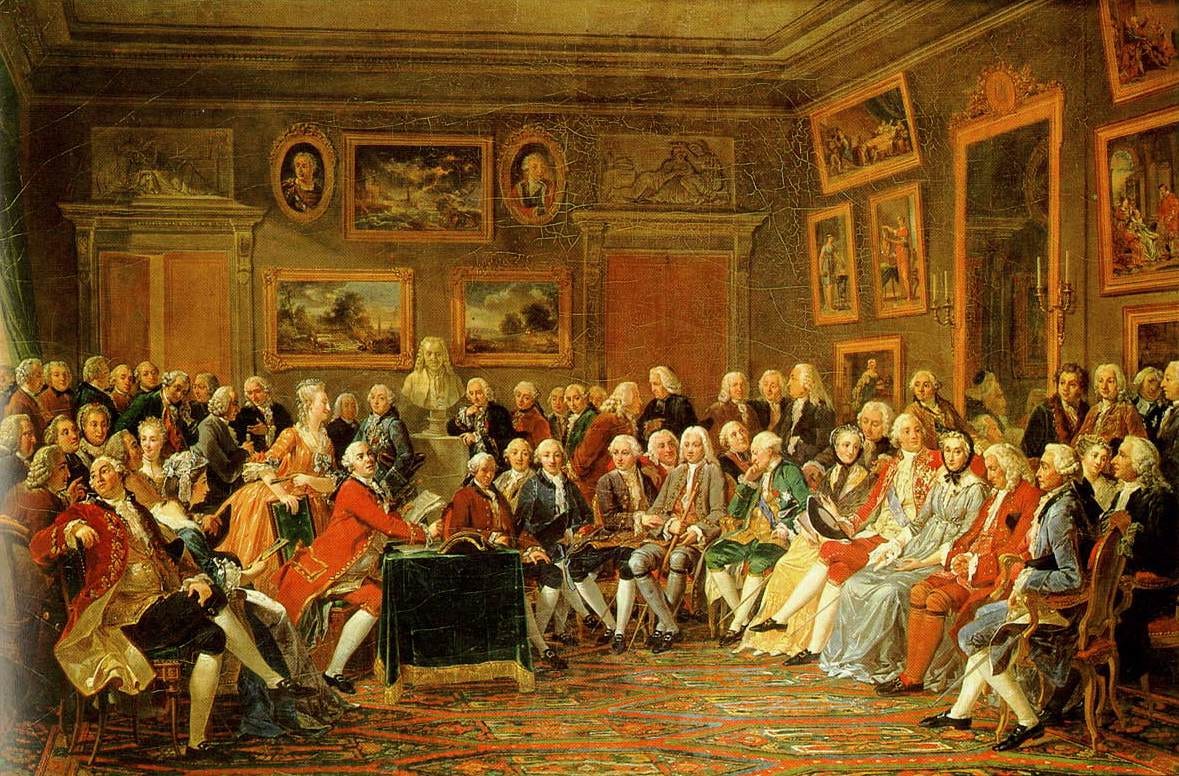

Interstate competition alone does not explain the acceleration of economic and technological development around 1800 as there was no obvious shock that might have greatly intensified competition between states in the 19th versus the 18th century. Instead, we should look at what was happening in Europe around that time: The European Enlightenment of the 17th and 18th centuries provided the intellectual basis underlying the institutions of modernity. For example, a society can gradually improve its institutions over the centuries due to external competition, but by the late 18th century, European political philosophy and the social sciences were already advanced to a point where the constitution of a state could be written from scratch up based on the principle that “All Men are Created Equal”. Thus, major institutional developments such as the English revolution of 1688, the American revolution of 1776, and the French Revolution of 1789 provided major breakthroughs in institutional quality that enabled the vastly increased speed of economic and technological development after 1800.

Among the revolutions, the French Revolution had perhaps the greatest impact as it broke down the autocratic political system of 18th century Europe’s greatest economic, cultural and scientific power and ultimately lead to its reformation into a modern constitutional republic with inclusive democratic institutions. Before the French Revolution, inclusive institutions were restricted to very small countries and city-states like the Dutch Republic and Florence, the Révolution opened the door for the implementation of modern institutions in a country of 30 million people. In the late 18th century that was a population 15 times larger than the Dutch Republic and 10 times larger than the US. Thanks to France’s massive cultural influence, over the decades after 1789, waves of constitutional reforms spread through Europe and, later, to the rest of the world, ultimately leading to the reformation of institutions worldwide from pre-modern autocracies into modern constitutional nation-states with more inclusive institutions.

Modern research also shows that the so-called “British industrial revolution” never existed on a macroeconomic scale, as from the late 18th century onward British economic performance never diverged from France’s. Instead, both countries achieved modern economic growth only after the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars that followed it:

It appears that, with the exception of Southern Europe, modern economic growth began everywhere in the West almost simultaneously and it did not take long to spread to the rest of the planet. For example, in Brazil’s case, we became de-facto independent following the French Revolution when Napoleon invaded Portugal. Formal independence came in 1822, then we started off as a rather autocratic monarchy called The Empire of Brazil for most of the 19th century. In 1889, our institutions evolved to those of a constitutional republic with very restrictive voting, to finally, a modern liberal democracy by the late 1980s, with 1989 being our first election where the entire adult population had the right to vote (that was roughly a century later than the UK and France had attained universal suffrage for males). Our system of law is directly based on French civil law, although many of the institutions of the Brazilian state are almost identical to the United States down to their dysfunctions. Brazil only achieved modern economic growth during the time when we became a republic, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, about a century later than the US and Northwestern Europe.

The Great Convergence

Life expectancy estimates suggest that the discrepancy in living standards between Western Europe and the US compared to Africa and Asia peaked in the 1920s and 1930s when the most advanced western countries had life expectancies of 60 to 65 years while life expectancy in Africa and Asia was around 20 to 30 years. But, by the mid-20th century, the process of global institutional development that was to eventually cause a strong tendency for convergence was already underway, and the global tendency for living standards to converge in the most advanced countries is apparent in life expectancy data for nearly a century:

In the case of China, it was its incorporation into the global system of international relations in the second half of the 19th century following the Opium Wars that started China’s process of convergence to the most advanced parts of the world. While the evidence suggests that incomes in China did not rise much from the late 19th century to the early 20th century, there were substantial improvements in the institutional, military, and technological spheres: Over this period the Chinese state changed from the so-called Qing Dynasty, an autocratic monarchy in the Pharaonic tradition, to the Republic of China, a modern constitutional nation-state (although still of the authoritarian rather than the democratic type). Military capabilities converged substantially to Western standards: In the mid-19th century, during the Opium Wars, France and the UK smashed the Chinese military as if they were stepping on ants, while a century later, the Chinese army proved itself effective against the US’s military in the Korean war. Although in the mid-20th century Chinese political institutions regressed back to autocratic absolutism during Mao’s reign. Thus, it was only after Deng Xiaoping’s reforms in the late 1970s that China finally experienced sustained economic growth. Today, China remains a poor country, with an income per capita of 30% of the level of the most developed countries but it has made tremendous progress in closing the gap in just a few decades.

An analogous but more salient process happened in Japan: Edo Japan was a typical centralized pre-modern civilization ruled by a single autocratic absolutist monarchy, just like Imperial China or Pharaonic Egypt. In the mid-19th century, Japan came into forced contact with the larger and more technologically sophisticated European-centered global civilization. Rationally evaluating their position in this newly globalized world, they quickly reformed their ways and adopted Western institutions, and as a result, Japan was the first non-European country that became a modern nation-state. After more than a century of explosive growth, its productivity reached 75% of the GDP per hour worked of the most advanced countries (France, Germany, and the US) by the end of the 20th century.

China was slower to converge to the West than Japan: Japan’s modernization began in the 1868 Meiji Restoration, while China’s modernizing reforms first came in 1911 with the founding of the Republic of China, and after a detour of a few decades into Mao’s totalitarianism, the big reforms came only in the 1970s. One might argue that China’s traditionally insular mentality (the country’s name in Chinese means “central kingdom”) played a major role in delaying their modernization but that delay might also be due to bad luck: The part of China that was not subjected to Marxist dictatorship, Taiwan, became a developed country only a couple of decades after Japan did so.

Most other parts of Asia and Africa became sovereign rather recently so they still did not have much time to converge to the frontier (apparently, being a colony is not good for convergence in economic development). The largest countries in Asia and Africa by population excluding China and Japan are India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Nigeria, these five countries all became independent from the late 1940s to 1960. All these countries developed tremendously after independence: Nigeria, the worst performer of this sample, saw its life expectancy increase from 37 to 55 years since independence in 1960.

How special is our modern economic growth?

It is often claimed that any sustained economic growth just did not exist at all before 1800, however, this claim is simply false. There are obvious counter-examples such as the dramatic growth in classical antiquity that I described in my previous post or the slow growth in the rate of urbanization of Europe from the Early Middle Ages up to 1800. In fact, the earliest documented literate cultures like Mesopotamia and Egypt over 4,000 years ago appear to have achieved a material culture that was much more complex than the material culture of hunter-gatherers despite their extremely high population densities. As Kron (2015) describes the housing standards in Bronze Age Egypt:

We can get some idea of the social inequality of Pharaonic, and presumably Achaemenid, Egypt by using housing as a proxy for income and studying the distribution of housing space in fully excavated towns, such as Middle Kingdom Kahun or New Kingdom Amarna (data from Kemp 1977). Here the vast majority of the population lived in small mud-brick houses with a median size of around 50 sq. meters, while the houses of high-ranking priests, scribes and officials, representing less than 8-10% of the dwellings, ranged from 150 or 200 sq. meters up to 750 or even 2500 sq. meters.

Thus, the top 8-10% of households in these ancient towns enjoyed sophisticated residential spaces, and even the median households despite very high levels of income inequality, enjoyed substantially better housing than the inhabitants of the poorest countries today, like Malawi:

While the Malthusian model might be a little too restrictive in its predictions to be consistent with the empirical evidence, it is fundamentally true that demographic trends and economic performance tend to be closely correlated over the long run. Periods of prosperity such as the last 200 years feature dramatic population growth while periods of economic depression feature population decline. Thus, the population growth rates over the very long term can give us an idea of the magnitude of historical economic growth.

In addition, there is a strong theoretical argument for long-run economic growth to be fundamentally constrained by population growth: Economic development depends on the creation of new ideas, and the population of human minds determines the potential rate of creation of ideas. Thus, over the very long run, population growth and the growth in income per person go hand in hand.

The world’s population increased at the rate of 1.17% per year from 1870 to 2020 (1870 is an important date in economic history: its the beginning of the “long-20th century” a time when modern economic growth started to have strong global effects), while over the thousand years from 800 to 1800, Europe’s population grew at a rate 0.17%, a growth rate of one-seventh of modern levels but still substantial. Ancient Greece provides the most impressive demographic expansion of pre-modernity: it is estimated from archeological field surveys that the population density in Greece proper grew from 3-4 inhabitants per square kilometer in 800 BC to 40-45 inhabitants in 300 BC, while the Greeks were colonizing many parts of the Mediterranean so that in the late 4th century BC, 40 to 45% of all Greeks lived outside of Greece proper (Hansen 2006). Thus the Greek population increased by a factor of ca. 17 to 23 times over 500 years which implies a growth rate of ca. 0.60%, much faster than the long-term rate of demographic expansion in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, and about as half as fast as the modern level which was achieved over the past 150 years.

From a global perspective, if we observe the evolution of the global population over the past 5,000 years on a logarithmic scale, it is clear it has grown at non-negligible rates over the millennia before 1800, despite the setbacks from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages (I actually made this graph aggregating estimates of the global population estimated by multiple demographers from the US Census website). Thus, it suggests that a very substantial fraction of the increase in economic complexity in world history occurred before the onset of modern economic growth.

Overall, it appears that both facts are true:

(1) There was substantial economic growth before modernity, but growth was geographically restricted to the areas of influence of individual civilizations.

(2) Economic growth since modernity has been faster and has been global. These two features are connected: Growth over a larger geographical area means growth affecting a greater number of people, which means more potential for creating ideas, which means faster growth.

References

Stephen Broadberry and Bishnupriya Gupta (2006). The Early Modern Great Divergence: Wages, Prices and Economic Development in Europe and Asia, 1500-1800. The Economic History Review, Vol. 59, No. 1, pp. 2-31.

Hansen, M. H. (2006), The Shotgun Method: The Demography of the Ancient Greek City State.

Kron, G. (2015), Growth and decline. Forms of Growth. Estimating growth in the Greek World in E. Lo Cascio, A. Bresson, F. Velde (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Economies in the Classical World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Morris, I. (2010). Why the West Rules―for Now: The Patterns of History, and What They Reveal About the Future. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, United States.

Pomeranz, D. (2000). The Great Divergence. Princeton University Press.

Schiedel, W. (2019), Escape from Rome, Princeton University Press.

Yi Xu, Bas van Leeuwen, Jan Luiten van Zanden (2018), Urbanization in China, ca. 1100–1900. Front. Econ. China , 13(3): 322–368.

A superb analysis of the highest quality.

Another great article! I love the US/Pakistan comparison as an illustration of how much of historical analysis is, kind of, a bunch of crap.