Ancient Inequality

Not only was the Classical Greek world likely more prosperous than the Roman world but also it was more egalitarian

In a previous piece, I argued why the present state of the evidence suggests that the Classical Greek world, around 500 to 200 BC, enjoyed higher living standards than the Early Imperial Roman world, which is often believed to be an exceptionally prosperous period in the pre-modern history of Western Eurasia (Europe, North Africa, and Western Asia). Here I enter more detail about the evidence we have for the distribution of material consumption and wealth in these societies.

Regarding antiquity, one thing we should keep in mind is that we only know about a tiny proportion of their records and written sources: among surviving historiographical sources for the Hellenistic period, only six volumes of a 40-volume work of Polybius survived to the present, and from ancient fragmentary evidence we know of the existence approximately 200 historians who wrote in the same period as Polybius. Reconstructing the ancient world from the literature that has survived to the present is analogous to aliens trying to reconstruct our modern world based on a few random non-fiction books plus the Harry Potter and the Lord of the Rings novels. Instead, I think that the archeological evidence might provide a more representative sample of how ancient societies functioned.

A tale of two towns: Olynthus and Pompeii

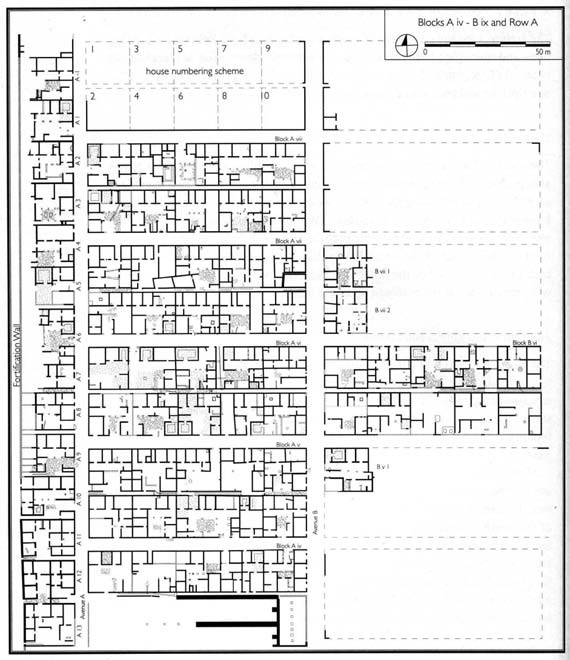

Consider two ancient towns: the Classical Greek town of Olynthus and the Imperial Roman town of Pompeii. Olynthus was a small Greek town covering 35 hectares; it was smaller than the average area encircled by walls among ancient Greek cities, although its size was likely close to the median. It was razed by the army of Phillip II in 348 BC; since it was destroyed, its excavated remains provide the best evidence we have of how typical Ancient Greeks lived during the golden age of their civilization.

Pompeii was an ancient Italian town not of Roman origin (like most of Roman Italy). It was incorporated as an “ally” of Rome in the early 3rd century BC, and it even went to war against Rome during the Social War in the early 1st century BC; remains of its walls still show the scars of Roman catapult fire during a siege by the Roman dictator Sulla. It was a town of slightly above-average size (with around 11-12 thousand inhabitants, it covered 65 hectares compared to the 53 hectares of average size for a Roman-era town estimated by Hanson 2016) that was destroyed by a volcanic eruption in 79 AD, and it represents the best photograph we have of how a prosperous Roman city functioned at the zenith of Roman power.

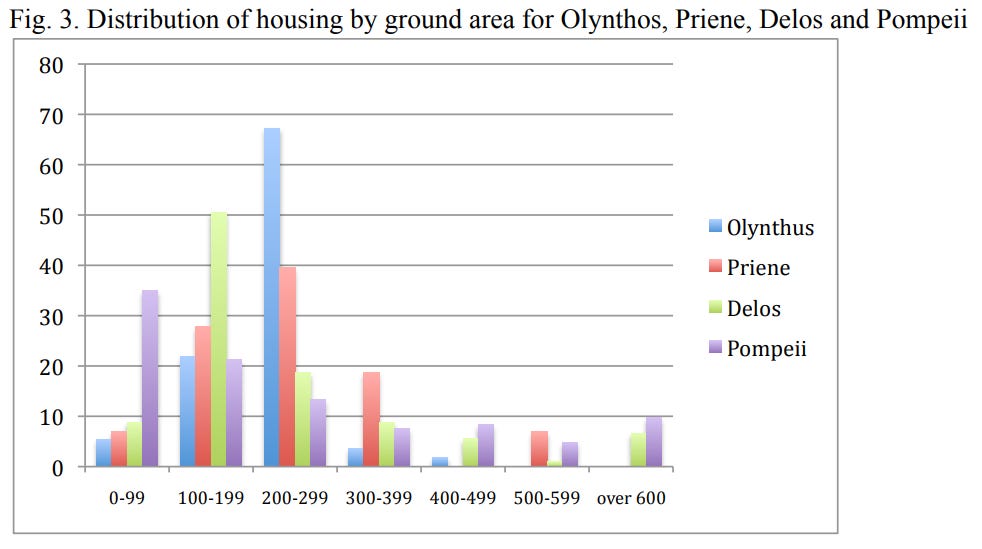

Interestingly, the average size of the first floor of the over 100 houses excavated from Olynthus (228 square meters) is approximately the same as a sample of 250 houses from Pompeii (240 square meters), which is consistent with the fact that both towns were very wealthy (in particular, living standards in Pompeii were much higher than in most Roman provinces), but the distribution of house sizes in Olynthus was very different from Pompeii’s, which reveals these two ancient towns had very distinct societies.

Olynthus shows that Classical Greek city-states were not only egalitarian in the sense it was common for its free male population to hold the rights for equal political participation (“democracy”) but also that households in Classical Greece typically achieved a similarly high level in their material standard of living: the vast majority of houses excavated by archeologists had sizes from 200 to 300 square meters.

Pompeii shows that the upper strata of Imperial Roman society achieved astonishing high levels of wealth but also that there were relatively few middle-class households and the majority of the population consisted of slaves and dependent families (intertwined in dependent relations with the richest families in what they called patronage), with living standards that were lower than the median in Classical Greece but still better than those of self-sufficient agricultural peasants in other pre-modern societies.

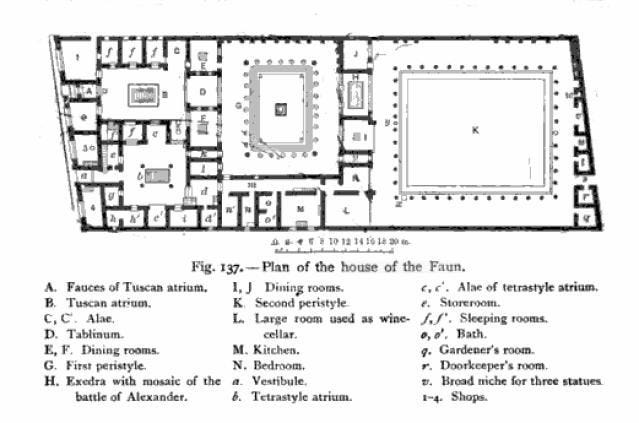

In Olynthus, 80% of the houses found by archeologists had a ground floor of between 200 and 400 square meters, while in Pompeii, the fraction of these “middle class” houses was only 20%. Instead, in Pompeii, there were enormous houses (like the palatial House of the Faun described by the plan below or this 3D reconstruction of another one), raising the average, while the vast majority of houses were substantially smaller than the typical “Oikos” house in Olynthus.

While Pompeii was separated by four centuries from Olynthus and belonged to a different culture, they are rather closely linked. Below is the picture of a mosaic found on the floor of the House of the Faun, which depicts Alexander, son of Phillip II (who razed down Olynthus), in battle around 333-331 BC, and is believed to be an attempt to replicate a famous Greek painting from the late 4th century BC. Rich Roman households loved Classical Greek art, and most of the evidence we have for high art in Classical antiquity consists of Roman copies of Classical originals:

Summarizing the evidence

The figure below from Kron (2015) shows the decline of the middle class during classical antiquity is documented by the best preserved and most intensively excavated ancient towns: the fraction of houses in the “middle-class” 200-400 square meters category was 80% in Olynthus (348 BC), 70% in Priene (ca. 3rd and 2nd centuries BC), less than 30% in Delos (1st and 2nd centuries BC and 1st century AD) and only 20% in Pompeii (79 AD). The Gini index of the distribution of house sizes was 0.14 for Olynthus, rising to 0.31 for Priene, 0.35 for Delos, and 0.54 for Pompeii.

Institutional changes in the Roman army reflected the collapse of the middle class during the Hellenistic period (321 BC to 31 BC): in Classical Greece, the bulk of the armies consisted of heavy infantry formations (the so-called hoplite phalanxes) that were manned by the middle-class citizens that were wealthy enough to afford heavy infantry equipment but not wealthy enough to afford horses. The armies of the Roman Republic followed the same basic pattern until the late 2nd century BC. By that point, the Roman army became fully professionalized because the Roman state was having difficulty finding many citizens with enough wealth to be able to purchase their own weapons and armor.

The increase in the proportion of citizens without property coincided with the increase in aggregate economic activity. Archeologists have found over 1,700 shipwrecks in the Mediterranean dating from before the 16th century. The vast majority of these shipwrecks were Roman, as the graph below describes the distribution of shipwrecks over 3,500 years from 2000 BC to 1500 AD:

One thing to keep in mind is that most archeological survey for shipwrecks was done in the Western Mediterranean (thanks to the fact it is directly next to Western Europe), which was the Latin-speaking half of the Roman Empire, while economic activity in the Greek-speaking Eastern half of the Mediterranean (a region that constituted 53% of the urban area of the Roman Empire according to the inventory of Roman cities in Hansen 2016) is underrepresented in the shipwreck sample. For example, note the rapid increase from the 3rd to the 2nd century BC: this increase followed the Roman victory over Hannibal in the 2nd Punic War, which resulted in the creation of a de-facto free trade area in the Western Mediterranean. Despite this bias, other archeological evidence of aggregate economic activity endorses the same trajectory for aggregate economic activity: an increase from 800 BC to a peak around 1 AD. For example, the study of heavy metal deposits in the Greenland icecaps shows that levels of heavy metal pollution achieved a peak in Late Republican and Imperial Roman times that was only surpassed in the 18th century. Another piece of evidence at the micro level consists of archeological field surveys. Surveys of regions in Italy and North Africa show that the density of archeological findings, such as pieces of broken pottery, reached a peak density from 100 BC to 200 AD (Wilson and Bowman 2009).

In the regions of the Classical Greek world, the economic trajectory was distinct from the Ancient World as a whole: the peak of material findings was during the period from 500 BC to 200 BC (Bresson 2016). Comparing the inventories of cities for the Classical Greek period in Hanson (2006) to the Roman period in Hansen (2016), it appears there was a decline of around 35% to 40% in the urbanized areas (estimated by the space enclosed inside city walls) of these regions. Despite their decline, the regions of the Classical Greek world remained a major component of the Roman world: one-quarter of the cities of the Roman Empire was located in these regions. In addition, following the conquests of Alexander the Great, the rest of the Eastern Mediterranean became heavily Hellenized, and the Greek cities founded in these areas (such as Alexandria in Egypt) reached their peak population levels during the Roman period. As a result, ca. 50% of the urban footprint of the Roman Empire consisted of cities that spoke Greek. As Italy did not pay any taxes to Rome (Rome declared all of Italy to be a tax-free region a couple of decades after Hannibal’s defeat), the bulk of the burden of paying the taxes supporting the city of Rome and its war machine fell on the Greek cities of the Eastern Mediterranean.

From the late 4th century BC to the Imperial Roman period, the middle class shrank, but the wealth of the richest citizens greatly increased: the famous Athenian orator Demosthenes living at the time of Alexander and Phillip II had inherited from his father a fortune worth 14 talents of silver or 85,000 drachmas, 65 times the value of a house of Zoilos in Olynthus; Demosthenes’ father was likely among the richest Athenian citizens considering he owned a knife factory, a furniture factory, and an armory, each of these small factories were said to be manned by dozens of slaves. The richest Athenian citizens were rumored to be worth 60 to 100 talents, and 9,000 Athenian citizens out of 31,000 had reported a net worth of over 1/3 of a talent (Kron 2011). Thus the richest Athenian citizens were worth about 200 to 300 times larger than the net worth of an Athenian citizen at the 70 percentile. For comparison, 200 times the wealth of the 70th percentile household in the US in 2020 (being at the 70th percentile in wealth in 2020 was 320 thousand dollars) is 60 million dollars. So there was a lot of inequality in the distribution of wealth in Classical Greece, even if this inequality was not reflected in the distribution of house sizes, as documented by archeologists.

By the mid-2nd century BC, at the time that Rome already was the dominant power of the ancient world, the richest Roman citizens had a net worth of around 200 talents, not much more than the richest Athenians two centuries earlier. As Roman power consolidated, fortunes multiplied, and century later, things were different: by the mid-1st century BC, Crassus was reportedly the richest Roman citizen and likely the owner of the largest private fortune in the world at the time. He was said to be worth 7,000 talents by Plutarch, or a hundred times the level of the richest Athenians nearly 300 years earlier. By the 1st century AD, at the time Pompeii was destroyed, the richest Roman senators had reported a net worth of around 10,000 to 13,000 talents of silver, roughly 150 times the wealth of the richest Athenian states. For comparison, the total annual salaries of the 400,000 soldiers in the Imperial Roman army by the late 1st century AD were estimated at 600 million sesterces or 20,000 talents of silver (Harper 2017).

In terms of silver, the unskilled wages in the Roman Empire were lower than in the Classical Greek world: laborers in Pompeii were paid a quarter of the rate of 4th century BC unskilled Athenian workers, and Alexander’s soldiers were paid roughly three times the rate of Roman legionaries four centuries later. In addition, while it was common for an Athenian citizen to own 2,000 drachmas of property, most Roman citizens were ploretarii without any wealth. Thus the wealth of the richest Roman senators was relative to the general population many hundreds of times larger than the wealth of the richest Athenians. The extraordinarily high wealth of the Roman elite was only made possible as the result of pan-Mediterranean economic growth from 800 BC to around 1 AD, combined with the Roman conquest and predation of the assets of the rest of the Ancient Mediterranean world (including plunder and taxation). That was so because Roman conquest enabled citizens to own property in many cities while the wealth of the richest Greeks, such as the richest Athenian citizens, was bounded by the size of the markets in their respective city-states. As Athens was one of the largest city-states, fortunes in smaller cities like Olynthus were even more strictly bounded.

Egalitarianism and inequality in consumption and wealth

There is no evidence that Classical Greek cities achieved their high degree of egalitarianism in terms of material consumption among their free citizens through social welfare programs that had the objective of achieving low levels of income inequality through large-scale redistribution of wealth. Although, I should point out that there is evidence for some welfare programs: Athens provided a pension for orphans of fathers killed in military service. In fact, the limited evidence we have is that Rome provided more social welfare than any Greek-city state with its “bread and circuses” policy of providing food and free public entertainment (a point made in Beard 2016). While there was substantial inequality in the distribution of wealth in Classical Greek cities, with the richest citizens being worth hundreds of times more than the median, this inequality was not very apparent in terms of material consumption.

Instead of being the product of large-scale centralized state intervention, a low level of material inequality should be expected in mature egalitarian societies: despite the allegedly high levels of wealth and income inequality in the current US and its relatively low degree of state redistribution compared to some European countries, if an American city were buried like Olynthus and Pompeii were, archeologists of the future would find that the material conditions of US households did not vary much, they would be like Olynthus instead of the huge variance in wealth displayed in the houses of Pompeii. Instead, most inequality in terms of wealth and income in the present US is reflected by the differential in premium rents paid for specific locations (for example, rents are about an order of magnitude higher in San Francisco for a physically identical place than in the typical suburb) or in expenditures for services like therapists, fancy colleges, and more expensive health insurance services, as well as expenditures in expensive art pieces.

If low levels of material inequality are natural in mature egalitarian societies, that implies that high levels of material inequality should be not stable (for example, the very high levels of material inequality during the late 19th century levels in Europe and the US did not survive longer than a couple of generations) or that societies with high levels of material inequality are not egalitarian in the sense that they do not treat their population as equal citizens under the law. In the case of Roman society, during the Republic, the Roman State attained high levels of popular participation, but Republican Rome never developed the concept that citizens had equal political rights, and thus, it never treated its citizens as equals under the law.

In Imperial Rome was a time when any pretense of popular political participation was gone. Due to its highly inegalitarian nature, elite citizens signaled their social position by building palatial houses and manning them with dozens of slaves and dependants. Most modern multi-millionaires in developed countries, in contrast, do not live in palaces with dozens of maids because doing so would be pointless. Similarly, in Classical Athens, while the richest citizens were hundreds of times richer than typical “middle class” citizens, they did not build massive palaces like the House of the Faun because it was regarded as being in bad taste and reminiscent of the decadence of the Persian King. At the same time, wages for unskilled workers in Classical Greece were much higher than in Imperial Rome, which enabled the median citizen to attain a much higher level of affluence. This explains why “middle-class” houses were so dominant in Olynthus and so rare in Pompeii.

I should point out that despite lacking the egalitarianism of Classical Greek societies, Roman society during the Late Republic and Early Empire was still quite mobile compared to other historical cultures: a freedman (a former slave) called Gaius Caecilius Claudius Isidorus, who died in 8 BC, included in his inheritance “4,116 slaves, 3,600 yoke of oxen, and 257,000 head of other kinds of cattle, besides in ready money 60,000,000 sesterces.” Pliny the Elder.

Note: I do not like the way the term “inequality” is used by laymen, social scientists, and the media to refer to higher or lower degrees of dispersion of income or wealth levels across the population. However, since everybody uses “income and wealth inequality" to describe the dispersion of incomes and wealth, I am following the convention in this article. One reason I do not like its current use is simple: 1 is unequal to 1.0001 in the same manner as one is unequal to a million, so it is mathematically inaccurate to use the term “higher inequality” to describe an increase in the dispersion of income or wealth. Another deeper, more significant reason is that the use of the word “inequality” to describe the distribution of wealth and income conflates the term with the idea of political equality. This is a very distinct concept: even the ancient greeks cities that adopted full direct democracy, such as Athens, did not (typically) conceive that maybe all the wealth could be redistributed so that everybody was “equal”; instead, they conceived that democracy as such that it gave equal political power to rich and poor alike. Using terms such as "wealth dispersion” or “income dispersion” is not only more accurate but also prevents the conflation of the idea that people are to be treated as equal citizens to the idea that people should have the exact same numerical figures in their bank accounts. In fact, the pursuit of the second concept is not feasible and directly contradicts the first.

References

Beard, M. (2016), SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome. Liveright.

Hansen, M. H. (2006), The Shotgun Method: The Demography of the Ancient Greek City State. University of Missouri Press.

Hanson, J.W. (2016), An urban geography of the Roman world, 100 BC to AD 300. Archaeopress.

Harper, K. (2017), The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire. Princeton University Press.

Kron (2015), Growth and decline. Forms of Growth. Estimating growth in the Greek World in E. Lo Cascio, A. Bresson, F. Velde (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Economies in the Classical World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

I would be interested to see a similar analysis of inequality levels in ancient Ionia compared with those ancient Athens. Since these were not slave societies, they should be more egalitarian and could help validate your thesis.

I'm not questioning the main thesis. It seems obvious that the Roman Empire was far more unequal than a greek town.

My question is how typical is Pompeii for a roman town? The presence of elites from Rome and their slaves throughout the Bay of Naples would greatly increase inequality unless there was a way for studies to control for these categories. Otherwise it's like comparing the Hamptons with an Iowa farm town.

My guess is that an average roman provincial agricultural town would be far more equal than Pompeii, but not as much as Olynthus.

While a poleis didn't had much welfare in normal times, often they did had laws to prevent the concentration of farm plots because they relied on small farmers for their levy, plus they might have had some form of heavier taxes for the rich, like equipping a naval ship.

Romans were usually pro-aristocracy so imperial laws would do nothing to prevent land concentration and high inequality.

Anyway, I rambled enough. Great post.